“In space no one can hear you scream,” the famous tagline from outer space horror classic “Alien,” might not be true based on a recent viral audio clip from NASA.

The 34-second clip of the sound a black hole makes was released in May but picked up steam online this week after NASA tweeted out what it’s calling a “Black Hole Remix.”

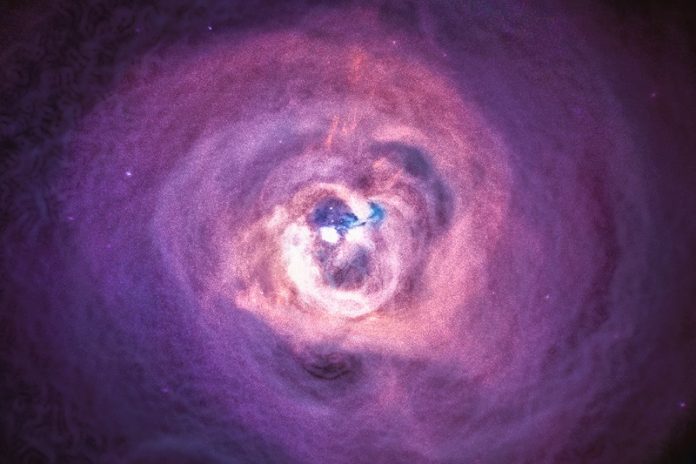

The sound, which evokes a deep spectral moan or some monstrous interstellar whale song, is based on a supermassive black hole located at the center of the Perseus galaxy cluster, located about 250 million light years from Earth.

The idea of recording audio from outer space is strange, since it’s commonly thought there is no sound in space. But this idea is a “popular misconception,” NASA said in a statement.

While much of space is a vacuum where sound can’t travel, a galaxy cluster like Perseus has enough hot gas to help serve as a medium for sound waves.

But something needs to cause those sound waves to move, and that’s where the black hole comes in.

“There’s all this hot gas surrounding the black hole, and the black hole is basically spitting out energy in some sort of periodic way––just like a speaker is moving in a periodic way–to give you some frequency,” says Jonathan Blazek, Northeastern assistant professor of physics.

“That means that essentially the gas is pushing against its neighboring gas and really propagating a physical sound wave out from the center.”

But how exactly did NASA capture the audio in the first place? It’s all part of NASA’s sonification project, which translates astronomical data into sound.

“We’re not capturing actual audio in space,” says Kim Arcand, NASA’s primary investigator on its sonification project.

“What we’re capturing is light; but we’re able to use that light to be able to understand that there are soundwaves occurring in this system.

In 2003, astronomers at NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory processed light taken in by the observatory’s telescope, capturing an image of the black hole and Perseus cluster.

But it was just an image, one that sat around for decades before NASA started its sonification program in 2020. Arcand, who has worked for Chandra for 25 years and now serves as its emerging technology lead, identified the image as the “perfect candidate” for the project.

From the original data, Arcand and her team were able to determine the density, temperature, wavelength and other key data points about the black hole and its environment.

That data is turned into a frequency, which, Arcand says, is “hundreds of piano keys farther south than what we can hear.” That’s where NASA’s remixed sonification comes into play.

“The idea is to bump up the frequency so that the pitch becomes high enough that humans can actually hear it,” Arcand says.

The sound required a lot of “bumping up.” The “note” emitted by the black hole was increased by 57 octaves in order to make it audible to the human ear.

“For reference, the A in the middle of the piano is 440 cycles per second, and this [sound] is one cycle per 10 million years,” Blazek says. “That’s where the 57 octaves come from––every octave is a doubling in frequency.”

Although the sound has been remixed to be audible, the sound itself is still largely consistent with the original sonic pattern, according to Blazek.

“I don’t think they’ve added a lot of junk,” he says. “In some sense, if we were gigantic beings with much, much larger ears and we lived for billions of years, we would actually hear something like this.”

Blazek is surprised the audio clip has found new life a couple months after it was first released. It speaks to NASA’s current moment–the James Webb Space Telescope found “smashing success,” Blazek says, with the first set of images NASA released over the summer. But it also may come down to the sound itself and how it fits into preconceptions of what black holes are.

“People often talk about black holes as monsters for good reason,” Blazek says. “They’re these giant unfeeling places where mass can never escape, and there’s something deeply horrifying about that in a philosophical sense, and the sound matches that.”

As for the broader implications of the audio clip, Blazek believes that renewed attention could create some useful crossover between analysis techniques for visual and audio data. And although he doesn’t see this “pretty old data” revealing anything new about black holes just yet, it could inspire work in the future around these interstellar monsters.

“To the extent that people are interested to actually think about sound waves and gasses in these sorts of environments, I think it could inspire new studies that will learn new things,” Blazek says.

Written by Cody Mello-Klein.

The misconception that there is no sound in space originates because most space is a ~vacuum, providing no way for sound waves to travel. A galaxy cluster has so much gas that we’ve picked up actual sound. Here it’s amplified, and mixed with other data, to hear a black hole! pic.twitter.com/RobcZs7F9e

— NASA Exoplanets (@NASAExoplanets) August 21, 2022