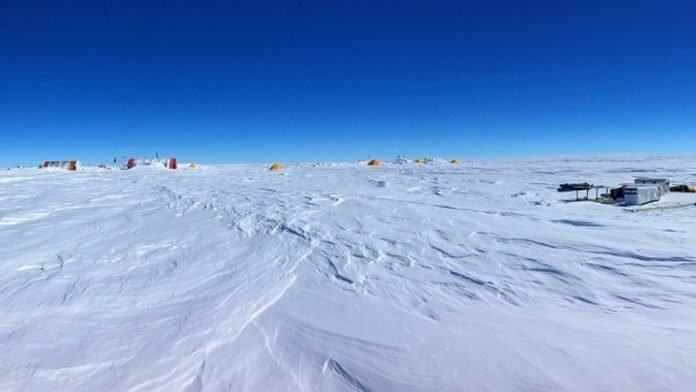

The worst effects of global warming on the world’s largest ice sheet could be avoided if nations around the world succeed in meeting climate targets outlined in the Paris Agreement.

That’s the call from an international team of climate scientists, including experts from The Australian National University (ANU) and the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), who have examined how much sea levels could rise if climate change melts the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS).

The team’s research, published in Nature, suggests by limiting global temperatures to well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the EAIS is predicted to add less than half a meter to sea-level rise by the year 2500.

If the targets aren’t met, sea-level rise from the EAIS alone could climb up to five meters in the same time period.

If greenhouse gas emissions are drastically scaled back and only a marginal rise in global warming is recorded, the research team predicts the EAIS – which holds the vast majority of Earth’s glacier ice – will likely not add to sea-level rise this century.

But the researchers say sea levels will still rise due to unstoppable ice losses from Greenland or West Antarctica.

The researchers warn if countries fail to meet Paris Climate Agreement targets, we risk awakening a “sleeping giant”.

“The EAIS is 10 times larger than West Antarctica and contains the equivalent of 52 metres of sea level,” co-author Professor Nerilie Abram, from the ANU Research School of Earth Sciences, said.

“If temperatures rise above two degrees Celsius beyond 2100, sustained by high greenhouse gas emissions, then East Antarctica alone could contribute around one to three metres to rising sea levels by 2300 and around two to five metres by 2500.”

Professor Abram said our window of opportunity to shield the world’s largest ice sheet from the impacts of climate change is quickly closing.

“A key lesson from the past is that the EAIS is highly sensitive to even relatively modest warming scenarios. It isn’t as stable and protected as we once thought,” she said.

“Achieving and strengthening our commitments to the Paris Agreement would not only protect the world’s largest ice sheet, but also slow the melting of other major ice sheets such as Greenland and West Antarctica, which are more vulnerable to global warming.”

Co-author Professor Matthew England, from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), said the projected increase in sea-level rise from the EAIS would add to rising sea levels caused by the thermal expansion of the ocean and the melting of ice elsewhere.

“Already, satellite observations show signs of thinning ice and its retreat,” he said.

“Our models show that the rate of ocean warming will only increase dramatically if we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Study co-author Professor Matt King from the University of Tasmania (UTas) said the study highlights how much work is needed to find out more about East Antarctica.

“We understand the Moon better than East Antarctica. So, we don’t yet fully understand the climate risks that will emerge from this area,” Professor King said.

The researchers examined how the EAIS responded to warm periods in Earth’s past and analysed projections made by existing studies in order to determine the impact of varying levels of future greenhouse gas emissions on the ice sheet by the years 2100, 2300 and 2500.

According to the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, published last year, human activity has already increased global mean temperatures by about 1.1 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times.

Professor Abram said by limiting global warming to well below two degrees Celsius, we can avoid the worst-case scenarios of global warming and even prevent major losses from the EAIS.

“We used to think East Antarctica was much less vulnerable to climate change, compared to the ice sheets in West Antarctica or Greenland, but we now know there are some areas of East Antarctica that are already showing signs of ice loss,” she said.

“This means the fate of the world’s largest ice sheet very much remains in our hands.”

This work was led by Durham University in the United Kingdom (UK) and is a collaboration between scientists from Australia, France, the US and the UK.