Powerful radio pulses originating deep in the cosmos can be used to study hidden pools of gas cocooning nearby galaxies, according to a new study appearing in the journal Nature Astronomy.

So-called fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are pulses of radio waves that typically originate millions to billions of light-years away.

Radio waves are electromagnetic radiation like the light we see with our eyes but have longer wavelengths and frequencies.

The first FRB was discovered in 2007, and since then, hundreds more have been found.

In 2020, Caltech’s STARE2 instrument (Survey for Transient Astronomical Radio Emission 2) and Canada’s CHIME (Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment) detected a massive FRB that went off in our own Milky Way galaxy.

Those earlier results helped confirm the theory that the energetic events most likely originate from dead, magnetized stars called magnetars.

As more and more FRBs roll in, researchers are now asking how they can be used to study the gas that lies between us and the bursts.

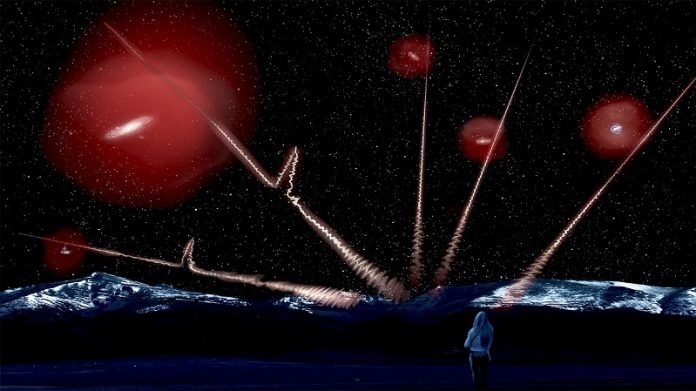

In particular, they would like to use the FRBs to probe halos of diffuse gas that surround galaxies.

As the radio pulses travel toward Earth, the gas enveloping the galaxies is expected to slow the waves down and disperse the radio frequencies.

In the new study, the researchers looked at a sample of 474 distant FRBs detected by CHIME, which has discovered the most FRBs to date, and showed that the subset of two dozen FRBs that passed through galactic halos were indeed slowed down more than non-intersecting FRBs.

“Our study shows that FRBs can act as skewers of all the matter between our radio telescopes and the source of the radio waves,” says lead author Liam Connor, the Tolman Postdoctoral Scholar Research Associate in Astronomy, who works with assistant professor of astronomy and study co-author, Vikram Ravi.

“We have used fast radio bursts to shine a light through the halos of galaxies near the Milky Way and measure their hidden material,” Connor says.

The study also reports finding more matter around the galaxies than expected—specifically, about twice as much gas as theoretical models predicted.

All galaxies are surrounded and fed by massive pools of gas out of which they were born. However, the gas is very thin and hard to detect.

“These gaseous reservoirs are enormous. If the human eye could see the spherical halo that surrounds the nearby Andromeda galaxy, the halo would appear one thousand times larger than the moon,” Connor says.

Researchers have developed different techniques to study the hidden halos.

For instance, Caltech professor of physics Christopher Martin and his team developed an instrument at the W. M. Keck Observatory called the Keck Cosmic Webb Imager (KCWI) that can probe the filaments of gas that stream into galaxies from the halos.

This new FRB method allows astronomers to measure the total amount of material in the halos, which will help piece together a picture of how galaxies grow and evolve over cosmic time.

“This is just the start,” says Ravi. “As we discover more FRBs, our techniques can be applied to study individual halos of different sizes and in different environments, addressing the unsolved problem of how matter is distributed in the universe.”

In the future, the FRB discoveries are expected to continue streaming in. Caltech’s 110-dish Deep Synoptic Array, or DSA-110, has already detected several FRBs and identified their host galaxies.

Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), this project is located at Caltech’s Owen Valley Radio Observatory near Bishop, California. In the coming years, Caltech researchers have plans to build an even bigger array, the DSA-2000, which will include 2,000 dishes and be the most powerful radio observatory ever built.

The DSA-2000, currently being designed with funding from Schmidt Futures and the NSF, will detect and identify the source of thousands of FRBs per year.

The Nature Astronomy is titled “The observed impact of halo gas on fast radio bursts.”

Written by Whitney Clavin.