Scientists have found a dormant stellar-mass black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy that neighbors the Milky Way.

The team includes Kareem El-Badry — nicknamed by fellow astronomers as the “black hole destroyer” — of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA).

“For the first time, our team got together to report on a black hole discovery, instead of rejecting one,” says study lead Tomer Shenar, a Marie-Curie Fellow at Amsterdam University in the Netherlands.

The team found that the star that gave rise to the black hole vanished without any sign of a powerful explosion.

“We identified a ‘needle in a haystack’,” says Shenar. Though other similar black hole candidates have been proposed, the team claims this is the first ‘dormant’ stellar-mass black hole to be unambiguously detected outside of the Milky Way galaxy.

The work was published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Stellar-mass black holes form when massive stars reach the end of their lives and collapse under their own gravity.

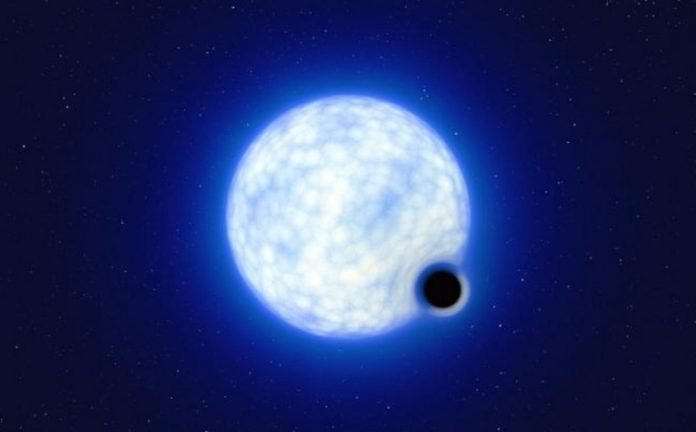

In a binary, a system of two stars revolving around each other, this process leaves behind a black hole in orbit with a luminous companion star. The black hole is ‘dormant’ if it does not emit high levels of X-ray radiation, which is how such black holes are typically detected.

The discovery was made thanks to six years of observations obtained with the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO’s) Very Large Telescope (VLT).

“It is incredible that we hardly know of any dormant black holes, given how common astronomers believe them to be”, explains co-author Pablo Marchant of KU Leuven.

The newly found black hole is at least nine times the mass of the Sun, and orbits a hot, blue star weighing 25 times the Sun’s mass.

Dormant black holes are particularly hard to spot since they do not interact much with their surroundings.

“For more than two years now, we have been looking for such black-hole-binary systems,” says co-author Julia Bodensteiner, a research fellow at ESO in Germany. “I was very excited when I heard about VFTS 243, which in my opinion is the most convincing candidate reported to date.”

To find VFTS 243, the collaboration searched nearly 1,000 massive stars in the Tarantula Nebula region of the Large Magellanic Cloud, looking for the ones that could have black holes as companions. Identifying these companions as black holes is extremely difficult, as so many alternative possibilities exist.

“As a researcher who has debunked potential black holes in recent years, I was extremely skeptical regarding this discovery,” says Shenar.

The skepticism was shared by CfA co-author El-Badry, whom Shenar calls the “black hole destroyer.” A recent Harvard Magazine story similarly calls El-Badry a “black hole debunker.”

“When Tomer asked me to double-check his findings, I had my doubts. But I could not find a plausible explanation for the data that did not involve a black hole,” explains El-Badry.

The discovery also allows the team a unique view into the processes that accompany the formation of black holes.

Astronomers believe that a stellar-mass black hole forms as the core of a dying massive star collapses, but it remains uncertain whether or not this is accompanied by a powerful supernova explosion.

“The star that formed the black hole in VFTS 243 appears to have collapsed entirely, with no sign of a previous explosion,” explains Shenar.

“Evidence for this ‘direct-collapse’ scenario has been emerging recently, but our study arguably provides one of the most direct indications. This has enormous implications for the origin of black-hole mergers in the cosmos.”

The black hole in VFTS 243 was found using six years of observations of the Tarantula Nebula by the Fibre Large Array Multi Element Spectrograph (FLAMES) instrument on ESO’s VLT. FLAMES allows astronomers to observe more than a hundred objects at once, a significant saving of telescope time compared to studying each object one by one.

Despite the nickname ‘black hole police,’ the team actively encourages scrutiny, and hope that their work will enable the discovery of other stellar-mass black holes orbiting massive stars, thousands of which are predicted to exist in Milky Way and in the Magellanic Clouds.

“Of course I expect others in the field to pore over our analysis carefully, and to try to cook up alternative models,” El-Badry says.

“It’s a very exciting project to be involved in.”

Source: Harvard-Smithsonian.