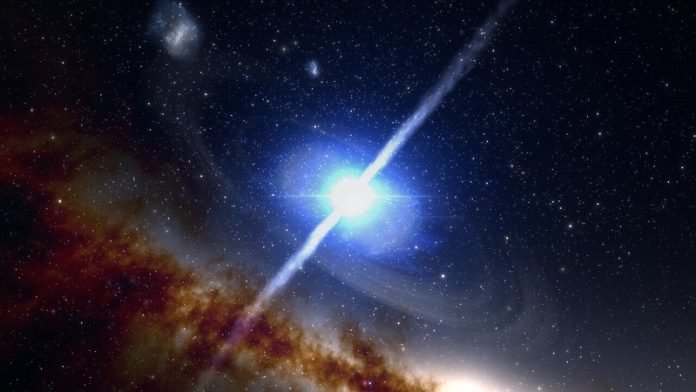

Several mysterious gamma-ray bursts appear as lonely flashes of intense energy far from any obvious galactic home, raising questions about their true origins and distances.

Using data from some of the most powerful telescopes on Earth and in space, including the twin Gemini telescopes, astronomers may have finally found their true origins — a population of distant galaxies, some nearly 10 billion light-years away.

An international team of astronomers has found that certain short gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) did not originate as castaways in the vastness of intergalactic space, as they initially appeared.

A deeper multi-observatory study instead found that these seemingly isolated GRBs actually occurred in remarkably distant — and therefore faint — galaxies up to 10 billion light-years away.

This discovery suggests that short GRBs, which form during the collisions of neutron stars, may have been more common in the past than expected. Since neutron-star mergers forge heavy elements, including gold and platinum, the Universe may have been seeded with precious metals earlier than expected.

This cosmic sleuthing required the combined power of some of the most powerful telescopes on Earth and in space, including the Gemini North telescope in Hawai‘i and the Gemini South telescope in Chile. The two Gemini telescopes comprise the International Gemini Observatory, operated by NSF’s NOIRLab.

Other observatories involved in this research include the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, the Lowell Discovery Telescope in Arizona, the Gran Telescopio Canarias in La Palma in the Canary Islands, ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Cerro Paranal in Chile, and the Keck Observatory in Hawai‘i.

“Many short GRBs are found in bright galaxies relatively close to us, but some of them appear to have no corresponding galactic home,” said Brendan O’Connor, first author of the paper presenting the results and an astronomer at both the University of Maryland and the George Washington University.

“By pinpointing where the short GRBs originate, we were able to comb through troves of data from observatories like the twin Gemini telescopes to find the faint glow of galaxies that were simply too distant to be recognized before.”

The researchers began their quest by reviewing data on 120 GRBs captured by two instruments aboard NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory: Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope, which signaled a burst had been detected; and Swift’s X-ray Telescope, which identified the general location of the GRB’s X-ray afterglow.

Additional afterglow studies made at Lowell Observatory more accurately pinpointed the location of the GRBs.

The afterglow studies found that 43 of the short GRBs were not associated with any known galaxy and appeared in the comparatively empty space between galaxies.

“These hostless GRBs presented an intriguing mystery and astronomers had proposed two explanations for their seemingly isolated existence,” said O’Connor.

One hypothesis was that the progenitor neutron stars formed as a binary pair inside a distant galaxy, drifted together into intergalactic space, and eventually merged billions of years later. The other hypothesis was that the neutron stars merged many billions of light-years away in their home galaxies, which now appear extremely faint as a result of their vast distance from Earth.

“We felt this second scenario was the most plausible to explain a large fraction of hostless events,” said O’Connor. “We then used the most powerful telescopes on Earth to collect deep images of the GRB locations and uncovered otherwise invisible galaxies 8 to 10 billion light-years away from Earth.”

To make these detections, the astronomers utilized a variety of optical and infrared instruments mounted on the twin 8.1-meter Gemini telescopes. Gemini Observatory offers the capability for observations from both hemispheres, which is incredibly important for GRB follow-up thanks to their ability to survey the entire sky. Gemini data were used to localize 17 out of 31 GRBs analyzed in their sample.

This result could help astronomers better understand the chemical evolution of the Universe. Merging neutron stars trigger a cascading series of nuclear reactions that are necessary to produce heavy metals, like gold, platinum, and thorium.

Pushing back the cosmic timescale on neutron-star mergers means that the young Universe was far richer in heavy elements than previously thought.

“This pushes the timescale back on when the Universe received the ‘Midas touch’ and became seeded with the heaviest elements on the periodic table,” said O’Connor.

“This survey for GRB host galaxies has delivered a compelling answer to the long-standing mystery of the nature of neutron star environments,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation.

“Among the largest open-access telescopes in the world, the Gemini Observatories provide powerful and flexible laboratories for a broad range of experiments and international collaboration.”