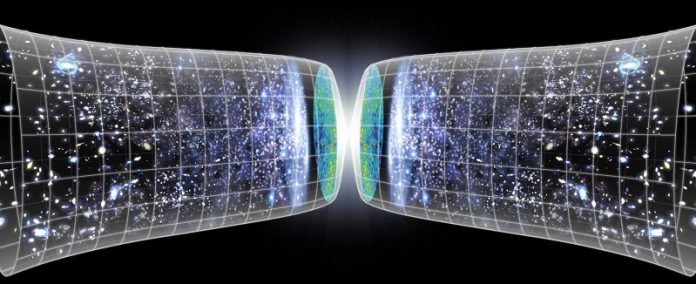

The idea of a mirror universe is a common trope in science fiction.

A world similar to ours where we might find our evil doppelganger or a version of us who actually asked out our high school crush.

But the concept of a mirror universe has been often studied in theoretical cosmology, and as a new study shows, it might help us solve problems with the cosmological constant.

The Hubble constant, or Hubble parameter, is a measure of the rate at which our universe expands.

This expansion was first demonstrated by Edwin Hubble, using data from Henrietta Leavitt, Vesto Slipher, and others.

Over the next several decades, measurements of this expansion settled on a rate of about 70 km/sec/Mpc. Give or take quite a bit.

Astronomers figured that as our measurements became precise, the various methods would settle on a common value, but that didn’t happen.

In fact, in the past several years measurements have become so precise they outright disagree. This is sometimes known as the cosmic tension problem.

At this point the observed values of the Hubble constant cluster into two groups.

Measurements of fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background point toward a lower value, around 67 km/sec/Mpc, while observations of objects such as distant supernovae yield a higher value around 73 km/sec/Mpc.

Something clearly doesn’t add up, and theoretical physicists are trying to figure out why. This is where the mirror universe might come in.

Wild ideas tend to fall in and out of popularity in theoretical physics. The mirror universe idea is no exception. It was studied quite a bit back in the 1990s as a way to deal with the problem of matter-antimatter symmetry.

We can create matter particles in the lab, but when we do, we also create antimatter particles.

They always come in pairs. So when particles formed in the early universe, where did all their antimatter siblings go? One idea was that the universe itself formed as a pair. Our matter universe and a similar antimatter universe.

Problem solved. The idea fell out of favor for various reasons, but this new study looks at how it might solve the Hubble problem.

The team discovered an invariance in what are known as unitless parameters.

The most famous of these is the fine structure constant, which has a value of about 1/137.

Basically, you can combine measured parameters in such a way that all the units cancel out, giving you the same number no matter what units you use, which is great if you are a theoretician.

The team found that when you tweak cosmological models to match the observed expansion rates, several unitless parameters stay the same, which suggests an underlying cosmic symmetry.

If you impose this symmetry more broadly, you can scale the rate of gravitational free-fall and the photon-electron scattering rate so that the different methods of Hubble measurement better agree.

And if this invariance is real, it implies the existence of a mirror universe. One that would affect our universe through a faint gravitational pull.

It should be pointed out that this study is mostly a proof of concept. It lays out how this cosmic invariance might solve the Hubble constant problem, but doesn’t go so far as to prove it’s a solution.

A more detailed model will be needed for that. But it’s an interesting idea.

And it’s good to know that if your evil doppelganger is out there, they can only influence your life gravitationally.

Written by Brian Koberlein.