Mars once ran red with rivers.

The telltale tracks of past rivers, streams and lakes are visible today all over the planet.

But about three billion years ago, they all dried up—and no one knows why.

“People have put forward different ideas, but we’re not sure what caused the climate to change so dramatically,” said University of Chicago geophysical scientist Edwin Kite.

“We’d really like to understand, especially because it’s the only planet we definitely know changed from habitable to uninhabitable.”

Kite is the first author of a new study that examines the tracks of Martian rivers to see what they can reveal about the history of the planet’s water and atmosphere.

Previously, many scientists had assumed that losing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which helped to keep Mars warm, caused the trouble.

But the new findings, published in Science Advances, suggest that the change was caused by the loss of some other important ingredient that maintained the planet warm enough for running water.

But we still don’t know what it is.

Water, water everywhere—and not a drop to drink

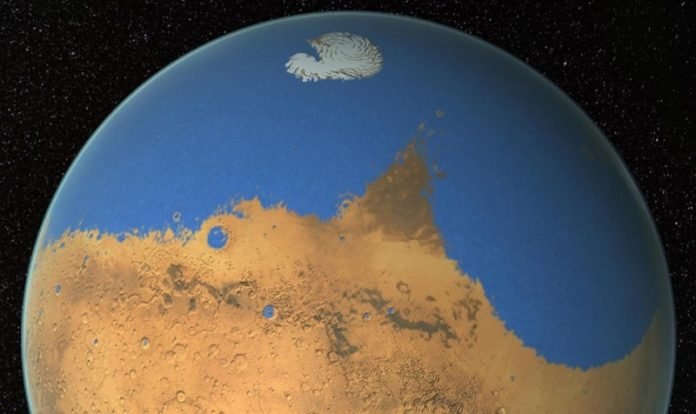

In 1972, scientists were astonished to see pictures from NASA’s Mariner 9 mission as it circled Mars from orbit. The photos revealed a landscape full of riverbeds—evidence that the planet once had plenty of liquid water, even though it’s dry as a bone today.

Since Mars doesn’t have tectonic plates to shift and bury the rock over time, ancient river tracks still lie on the surface like evidence abandoned in a hurry.

This allowed Kite and his collaborators, including University of Chicago graduate student Bowen Fan as well as scientists from the Smithsonian Institution, Planetary Science Institute, California Institute of Technology Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Aeolis Research, to analyze maps based on thousands of pictures taken from orbit by satellites.

Based on which tracks overlap which, and how weathered they are, the team pieced together a timeline of how river activity changed in elevation and latitude over billions of years.

Then they could combine that with simulations of different climate conditions, and see which matched best.

Planetary climates are enormously complex, with many, many variables to account for—especially if you want to keep your planet in the “Goldilocks” zone where it’s exactly warm enough for water to be liquid but not so hot that it boils.

Heat can come from a planet’s sun, but it has to be near enough to receive radiation but not so near that the radiation strips away the atmosphere.

Greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, can trap heat near a planet’s surface. Water itself plays a role, too; it can exist as clouds in the atmosphere or as snow and ice on the surface. Snowcaps tend to act as a mirror to reflect away sunlight back into space, but clouds can either trap or reflect away light, depending on their height and composition.

Kite and his collaborators ran many different combinations of these factors in their simulations, looking for conditions that could cause the planet to be warm enough for at least some liquid water to exist in rivers for more than billion years—but then abruptly lose it.

But as they compared different simulations, they saw something surprising. Changing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere didn’t change the outcome. That is, the driving force of the change didn’t seem to be carbon dioxide.

“Carbon dioxide is a strong greenhouse gas, so it really was the leading candidate to explain the drying out of Mars,” said Kite, an expert on the climates of other worlds. “But these results suggest it’s not so simple.”

There are several alternative options.

The new evidence fits nicely with a scenario, suggested in a 2021 study from Kite, where a layer of thin, icy clouds high in Mars’ atmosphere acts like translucent greenhouse glass, trapping heat. Other scientists have suggested that if hydrogen was released from the planet’s interior, it could have interacted with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to absorb infrared light and warm the planet.

“We don’t know what this factor is, but we need a lot of it to have existed to explain the results,” Kite said.

There are a number of ways to try to narrow down the possible factors; the team suggests several possible tests for NASA’s Perseverance rover to perform that could reveal clues.

Kite and colleague Sasha Warren are also part of the science team that will be directing NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover to search for clues about why Mars dried out. They hope that these efforts, as well as measurements from Perseverance, can provide additional clues to the puzzle

On Earth, many forces have combined to keep the conditions remarkably stable for millions of years. But other planets may not be so lucky.

One of the many questions scientists have about other planets is exactly how lucky we are—that is, how often this confluence exists occurs in the universe. They hope that studying what happened to other planets, such as Mars, can yield clues about planetary climates and how many other planets out there might be habitable.

“It’s really striking that we have this puzzle right next door, and yet we’re still not sure how to explain it,” said Kite.

Written by Louise Lerner.