In studying a unique class of ultra-hot exoplanets, NASA Hubble Space Telescope astronomers may be in the mood for dancing to the Calypso party song “Hot, Hot, Hot.”

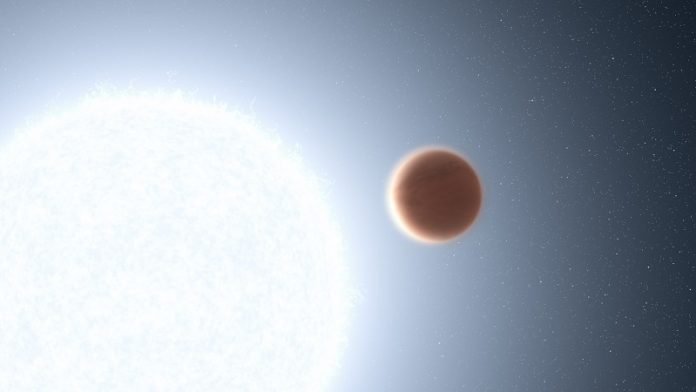

That’s because these bloated Jupiter-sized worlds are so precariously close to their parent star they are being roasted at seething temperatures above 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

That’s hot enough to vaporize most metals, including titanium. They have the hottest planetary atmospheres ever seen.

In two new papers, teams of Hubble astronomers are reporting on bizarre weather conditions on these sizzling worlds.

It’s raining vaporized rock on one planet, and another one has its upper atmosphere getting hotter rather than cooler because it is being “sunburned” by intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation from its star.

This research goes beyond simply finding weird and quirky planet atmospheres.

Studying extreme weather gives astronomers better insights into the diversity, complexity, and exotic chemistry taking place in far-flung worlds across our galaxy.

“We still don’t have a good understanding of weather in different planetary environments,” said David Sing of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, co-author on two studies being reported.

“When you look at Earth, all our weather predictions are still finely tuned to what we can measure.

But when you go to a distant exoplanet, you have limited predictive powers because you haven’t built a general theory about how everything in an atmosphere goes together and responds to extreme conditions.

Even though you know the basic chemistry and physics, you don’t know how it’s going to manifest in complex ways.”

In a paper in the April 7 journal Nature, astronomers describe Hubble observations of WASP-178b, located about 1,300 light-years away. On the daytime side the atmosphere is cloudless, and is enriched in silicon monoxide gas.

Because one side of the planet permanently faces its star, the torrid atmosphere whips around to the nighttime side at super-hurricane speeds exceeding 2,000 miles per hour.

On the dark side, the silicon monoxide may cool enough to condense into rock that rains out of clouds, but even at dawn and dusk, the planet is hot enough to vaporize rock.

“We knew we had seen something really interesting with this silicon monoxide feature,” said Josh Lothringer of the Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah.

In a paper published in the January 24 issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters, Guangwei Fu of the University of Maryland, College Park, reported on a super-hot Jupiter, KELT-20b, located about 400 light-years away.

On this planet a blast of ultraviolet light from its parent star is creating a thermal layer in the atmosphere, much like Earth’s stratosphere.

“Until now we never knew how the host star affected a planet’s atmosphere directly. There have been lots of theories, but now we have the first observational data,” Fu said.

By comparison, on Earth, ozone in the atmosphere absorbs UV light and raises temperatures in a layer between 7 to 31 miles above Earth’s surface.

On KELT-20b the UV radiation from the star is heating metals in the atmosphere which makes for a very strong thermal inversion layer.

Evidence came from Hubble’s detection of water in near-infrared observations, and from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope’s detection of carbon monoxide.

They radiate through the hot, transparent upper atmosphere that is produced by the inversion layer. This signature is unique from what astronomers see in the atmospheres of hot-Jupiters orbiting cooler stars, like our Sun.

“The emission spectrum for KELT-20b is quite different from other hot-Jupiters,” said Fu. “This is compelling evidence that planets don’t live in isolation but are affected by their host star.”

Though super-hot Jupiters are uninhabitable, this kind of research helps pave the way to better understanding the atmospheres of potentially inhabitable terrestrial planets.

“If we can’t figure out what’s happening on super-hot Jupiters where we have reliable solid observational data, we’re not going to have a chance to figure out what’s happening in weaker spectra from observing terrestrial exoplanets,” said Lothringer.

“This is a test of our techniques that allows us to build a general understanding of physical properties such as cloud formation and atmospheric structure.”