It all started around 13.8 billion years ago with a big, cosmological “bang” that brought the universe suddenly and spectacularly into existence.

Shortly after, the infant universe cooled dramatically and went completely dark.

Then, within a couple hundred million years after the Big Bang, the universe woke up, as gravity gathered matter into the first stars and galaxies.

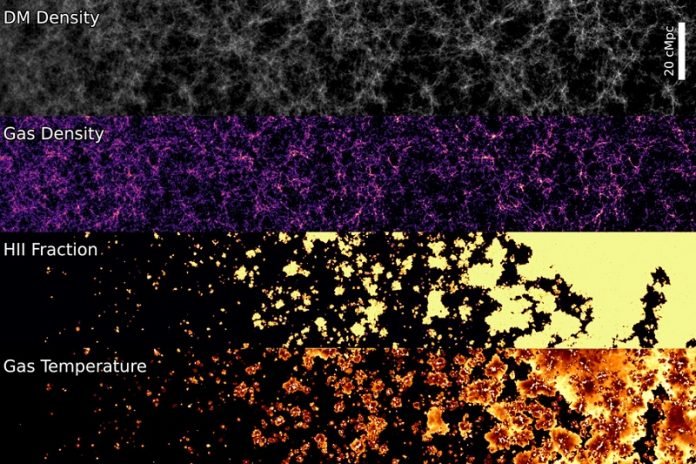

Light from these first stars turned the surrounding gas into a hot, ionized plasma — a crucial transformation known as cosmic reionization that propelled the universe into the complex structure that we see today.

Now, scientists can get a detailed view of how the universe may have unfolded during this pivotal period with a new simulation, known as Thesan, developed by scientists at MIT, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

Named after the Etruscan goddess of the dawn, Thesan is designed to simulate the “cosmic dawn,” and specifically cosmic reionization, a period which has been challenging to reconstruct, as it involves immensely complicated, chaotic interactions, including those between gravity, gas, and radiation.

The Thesan simulation resolves these interactions with the highest detail and over the largest volume of any previous simulation.

It does so by combining a realistic model of galaxy formation with a new algorithm that tracks how light interacts with gas, along with a model for cosmic dust.

With Thesan, the researchers can simulate a cubic volume of the universe spanning 300 million light years across.

They run the simulation forward in time to track the first appearance and evolution of hundreds of thousands of galaxies within this space, beginning around 400,000 years after the Big Bang, and through the first billion years.

So far, the simulations align with what few observations astronomers have of the early universe. As more observations are made of this period, for instance with the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, Thesan may help to place such observations in cosmic context.

For now, the simulations are starting to shed light on certain processes, such as how far light can travel in the early universe, and which galaxies were responsible for reionization.

“Thesan acts as a bridge to the early universe,” says Aaron Smith, a NASA Einstein Fellow in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “It is intended to serve as an ideal simulation counterpart for upcoming observational facilities, which are poised to fundamentally alter our understanding of the cosmos.”

Smith and Mark Vogelsberger, associate professor of physics at MIT, Rahul Kannan of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Enrico Garaldi at Max Planck have introduced the Thesan simulation through three papers, the third published today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow the light

In the earliest stages of cosmic reionization, the universe was a dark and homogenous space. For physicists, the cosmic evolution during these early “dark ages” is relatively simple to calculate.

“In principle you could work this out with pen and paper,” Smith says. “But at some point gravity starts to pull and collapse matter together, at first slowly, but then so quickly that calculations become too complicated, and we have to do a full simulation.”

To fully simulate cosmic reionization, the team sought to include as many major ingredients of the early universe as possible.

They started off with a successful model of galaxy formation that their groups previously developed, called Illustris-TNG, which has been shown to accurately simulate the properties and populations of evolving galaxies.

They then developed a new code to incorporate how the light from galaxies and stars interact with and reionize the surrounding gas — an extremely complex process that other simulations have not been able to accurately reproduce at large scale.

“Thesan follows how the light from these first galaxies interacts with the gas over the first billion years and transforms the universe from neutral to ionized,” Kannan says. “This way, we automatically follow the reionization process as it unfolds.”

Finally, the team included a preliminary model of cosmic dust — another feature that is unique to such simulations of the early universe. This early model aims to describe how tiny grains of material influence the formation of galaxies in the early, sparse universe.

Cosmic bridge

With the simulation’s ingredients in place, the team set its initial conditions for around 400,000 years after the Big Bang, based on precision measurements of relic light from the Big Bang.

They then evolved these conditions forward in time to simulate a patch of the universe, using the SuperMUC-NG machine — one of the largest supercomputers in the world — which simultaneously harnessed 60,000 computing cores to carry out Thesan’s calculations over an equivalent of 30 million CPU hours (an effort that would have taken 3,500 years to run on a single desktop).

The simulations have produced the most detailed view of cosmic reionization, across the largest volume of space, of any existing simulation. While some simulations model across large distances, they do so at relatively low resolution, while other, more detailed simulations do not span large volumes.

“We are bridging these two approaches: We have both large volume and high resolution,” Vogelsberger emphasizes.

Early analyses of the simulations suggest that towards the end of cosmic reionization, the distance light was able to travel increased more dramatically than scientists had previously assumed.

“Thesan found that light doesn’t travel large distances early in the universe,” Kannan says. “In fact, this distance is very small, and only becomes large at the very end of reionization, increasing by a factor of 10 over just a few hundred million years.”

The researchers also see hints of the type of galaxies responsible for driving reionization. A galaxy’s mass appears to influence reionization, though the team says more observations, taken by James Webb and other observatories, will help to pin down these predominant galaxies.

“There are a lot of moving parts in [modeling cosmic reionization],” Vogelsberger concludes. “When we can put this all together in some kind of machinery and start running it and it produces a dynamic universe, that’s for all of us a pretty rewarding moment.”

This research was supported in part by NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the Gauss Center for Supercomputing.

Written by Jennifer Chu