Small electronics, including smartwatches and fitness trackers, aren’t easily dismantled and recycled.

So when a new model comes out, most users send the old devices into hazardous waste streams.

To simplify small electronics recycling, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have developed a two-metal nanocomposite for circuits that disintegrates when submerged in water.

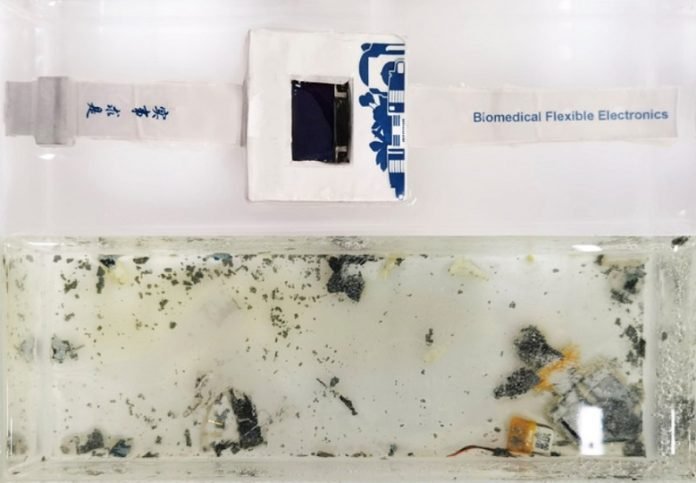

They demonstrated the circuits in a prototype transient device — a functional smartwatch that dissolved within 40 hours.

Planned obsolescence and the fast pace of technology innovations leads to new devices that are continuously replacing old versions, which generates millions of tons of electronic waste per year.

Recycling can reduce the volume of e-waste and is mandatory in many places.

However, it often isn’t worth the effort to recycle small consumer electronics because their parts must be salvaged by hand, and some processing steps, such as open burning and acid leaching, can cause health issues and environmental pollution.

Dissolvable devices that break apart on demand could solve both of those problems.

Previously Xian Huang and colleagues developed a zinc-based nanocomposite that dissolved in water for use in temporary circuits, but it wasn’t conductive enough for consumer electronics.

So, they wanted to improve their dissolvable nanocomposite’s electrical properties while also creating circuits robust enough to withstand everyday use.

The researchers modified the zinc-based nanocomposite by adding silver nanowires, making it highly conductive.

Then, they screen-printed the metallic solution onto pieces of poly(vinyl alcohol) — a polymer that degrades in water — and solidified the circuits by applying small droplets of water that facilitate chemical reactions and then evaporate.

With this approach, the team made a smartwatch with multiple nanocomposite-printed circuit boards inside a 3D printed poly(vinyl alcohol) case.

The smartwatch had sensors that accurately measured a person’s heart rate, blood oxygen levels and step count, and sent the information to a cellphone app via a Bluetooth connection.

The outer package held up to sweat, but once the whole device was fully immersed in water, both the polymer case and circuits dissolved completely within 40 hours.

All that was left behind were the watch’s components, such as an organic light-emitting diode (OLED) screen and microcontroller, as well as resistors and capacitors that had been integrated into the circuits.

The researchers say the two-metal nanocomposite can be used to produce transient devices with performance matching that of commercial models, which could go a long way toward solving the challenges of small electronics waste.

The abstract that accompanies this paper can be viewed here.