A new study disputes the prevailing hypothesis on why Mercury has a big core relative to its mantle (the layer between a planet’s core and crust).

For decades, scientists argued that hit-and-run collisions with other bodies during the formation of our solar system blew away much of Mercury’s rocky mantle and left the big, dense, metal core inside.

But new research reveals that collisions are not to blame–the sun’s magnetism is.

William McDonough, a professor of geology at the University of Maryland, and Takashi Yoshizaki from Tohoku University developed a model showing that the density, mass and iron content of a rocky planet’s core are influenced by its distance from the sun’s magnetic field.

The paper describing the model was published in the journal Progress in Earth and Planetary Science.

“The four inner planets of our solar system–Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars–are made up of different proportions of metal and rock,” McDonough said.

“There is a gradient in which the metal content in the core drops off as the planets get farther from the sun.

Our paper explains how this happened by showing that the distribution of raw materials in the early forming solar system was controlled by the sun’s magnetic field.”

McDonough previously developed a model for Earth’s composition that is commonly used by planetary scientists to determine the composition of exoplanets. (His seminal paper on this work has been cited more than 8,000 times.)

McDonough’s new model shows that during the early formation of our solar system, when the young sun was surrounded by a swirling cloud of dust and gas, grains of iron were drawn toward the center by the sun’s magnetic field.

When the planets began to form from clumps of that dust and gas, planets closer to the sun incorporated more iron into their cores than those farther away.

The researchers found that the density and proportion of iron in a rocky planet’s core correlates with the strength of the magnetic field around the sun during planetary formation.

Their new study suggests that magnetism should be factored into future attempts to describe the composition of rocky planets, including those outside our solar system.

The composition of a planet’s core is important for its potential to support life. On Earth, for instance, a molten iron core creates a magnetosphere that protects the planet from cancer-causing cosmic rays.

The core also contains the majority of the planet’s phosphorus, which is an important nutrient for sustaining carbon-based life.

Using existing models of planetary formation, McDonough determined the speed at which gas and dust was pulled into the center of our solar system during its formation.

He factored in the magnetic field that would have been generated by the sun as it burst into being and calculated how that magnetic field would draw iron through the dust and gas cloud.

As the early solar system began to cool, dust and gas that were not drawn into the sun began to clump together.

The clumps closer to the sun would have been exposed to a stronger magnetic field and thus would contain more iron than those farther away from the sun.

As the clumps coalesced and cooled into spinning planets, gravitational forces drew the iron into their core.

When McDonough incorporated this model into calculations of planetary formation, it revealed a gradient in metal content and density that corresponds perfectly with what scientists know about the planets in our solar system.

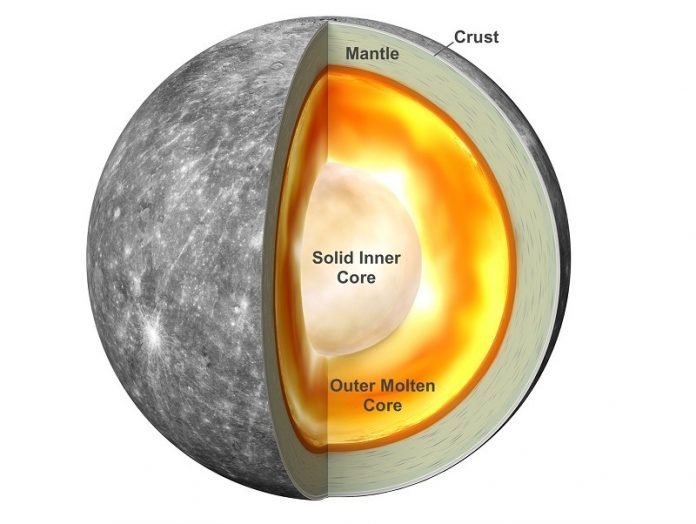

Mercury has a metallic core that makes up about three-quarters of its mass. The cores of Earth and Venus are only about one-third of their mass, and Mars, the outermost of the rocky planets, has a small core that is only about one-quarter of its mass.

This new understanding of the role magnetism plays in planetary formation creates a kink in the study of exoplanets, because there is currently no method to determine the magnetic properties of a star from Earth-based observations.

Scientists infer the composition of an exoplanet based on the spectrum of light radiated from its sun.

Different elements in a star emit radiation in different wavelengths, so measuring those wavelengths reveals what the star, and presumably the planets around it, are made of.

“You can no longer just say, ‘Oh, the composition of a star looks like this, so the planets around it must look like this,'” McDonough said. “Now you have to say, ‘Each planet could have more or less iron based on the magnetic properties of the star in the early growth of the solar system.'”

The next steps in this work will be for scientists to find another planetary system like ours–one with rocky planets spread over wide distances from their central sun.

If the density of the planets drops as they radiate out from the sun the way it does in our solar system, researchers could confirm this new theory and infer that a magnetic field influenced planetary formation.