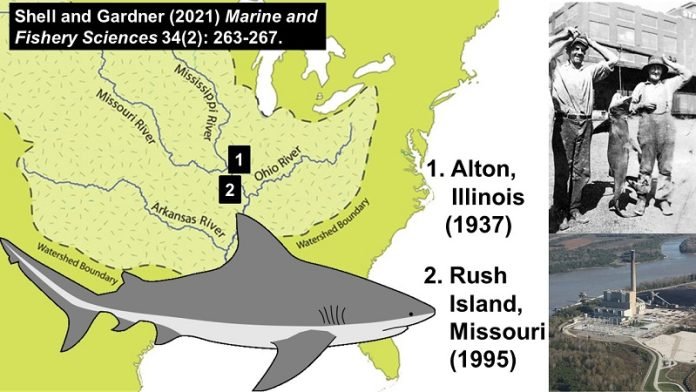

For many people, the idea of sharks in the upper Mississippi River would seem laughable, yet they have been caught here at least twice– once in 1937 and again in 1995.

In both cases, bull sharks managed to swim upstream past St. Louis, Missouri, more than 1,160 river miles from the Gulf of Mexico where they are normally found.

Bull sharks are one of the few shark species known to swim in freshwater, and do travel substantially inland in tropical freshwater around the world (Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America).

When it comes to the Mississippi River, however, most sightings are found downstream from the Arkansas-Louisiana state line (south of the 33rd parallel north).

These far inland sightings intrigued paleontologist Dr. Ryan Shell (A research associate at the Cincinnati Museum Center)– could bull sharks be regularly swimming upstream in the Mississippi, even into the upper portion, without being detected?

He enlisted the help of a colleague, WVU Potomac State College librarian Nick Gardner, to dig into historical records and modern sightings. Together they poured through numerous accounts, ruling out most as hoaxes or misidentifications, but were left with two indisputable ones.

In 1937, a five-foot-long bull shark was caught by two fishermen at Alton, Illinois. This is the farthest inland a shark has been known to travel within the Mississippi River.

Numerous other investigators have studied the case and have concluded it was verifiable. The other sighting, less commonly known, was in 1995 when a bull shark was found caught in a grate at the Rush Island Power Station near St. Louis, Missouri.

“The 1937 sighting seems to be the cause for people jumping to a bull shark identification whenever they think they’ve spotted a shark on the Mississippi,” said Gardner.

“In most cases, we found that if it wasn’t an outright hoax, it was never a bull shark, more often it was a case of a shark being caught in the Gulf that was dumped from a boat, or a total misidentification of a freshwater fish.”

Worse than these misidentifications are the cases that were outright fabrications, such as the supposed finding of bull shark teeth by a young girl in Minnehaha Creek, Minnesota in 2005. In that case, what was intended as an April Fool’s joke on a homeowner’s association website ended up out of control.

This story spread across the Internet through discussion boards, ultimately being reported numerous times by news outlets as factual, and social media has only increased its spread.

“The persistence of the Minnehaha Creek story is a lesson unto itself on how unreliable information can spread online,” said Gardner who teaches students how to find and use information online, “This project really intrigued me as a model for how fake news can mislead and appear credible and I think it deserves further study– we’ve written up the biology side, but not the sociology side.”

Fake shark stories seem to easily go viral since they tie into a deep fear many people have of sharks — in spite of that only ten people had fatal encounters with sharks in 2020, far less than the number who died from lightning, lawnmowers, and sundry other circumstances.

And as far as the facts go through regarding bull sharks, Shell and Gardner couldn’t rule out their ability to traverse into the upper Mississippi River basin — finding that factors often cited as possible barriers, such as temperature, could not be substantiated.

“Instead, we found that bull sharks actually have a wide tolerance for different temperatures,” said Shell, “In fact, much of the lower portion of the upper Mississippi River experience favorable temperatures for these sharks throughout large portions of the year.”

Shell and Gardner are left with more questions than answers. Shell said, “We don’t understand how physical barriers like dams and locks play a role, if at all, or what may motivate the sharks to move upstream; we can answer what, when, and where that sharks did this, but not how or why.”

Getting out to the field to answer this may not make it much easier–In rivers, Bull sharks appear to exhibit cryptic behavior such as swimming along the bottom during the daytime which would make them more difficult to spot, and water visibility is generally poor along much of the Mississippi River.

Locks which were thought to limit the sharks’ ability to travel, don’t seem to halt similarly sized or larger fishes such as gars or sturgeons from moving up the Mississippi River and Bull sharks seem to navigate locks just fine elsewhere in the world.

Shell noted, “It’s easy to dismiss these cases as one-off events, but that ignores the interesting question of how these animals evaded detection and got so far upstream in the first place.”

They didn’t limit themselves to the recent either — they also reviewed what was known from archaeological and fossil records, but didn’t find much evidence that shed light on the question.

According to Shell, “Often the archaeological reports of shark teeth don’t provide useful sketches or photographs, if any at all, and effort is not made to identify them convincingly to the species level.”

This is a problem because shark teeth are not unusual in many archaeological sites, especially in the Ohio River Valley portion of the upper Mississippi River Basin.

These teeth were apparently desirable for indigenous trade, so it would be hard to ever establish if they had been sourced from the Atlantic or Gulf coasts or from a shark that somehow made its way up the Mississippi.

Shell and Gardner’s findings appear in Marine and Fishery Sciences.

Gardner noted it was very important to them that their research be easily accessed by others — “Our research has left us with more questions than answers, so our hope is to start a dialogue around Bull shark behavior and encourage others to join us in exploring the problem.”

Shell is now a paleontological resources assistant for the US Forest Service in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. He completed his Ph.D. at Wright State University in 2020 studying fossil sharks.

He has previously taught at the University of Dayton and Wright State University. Shell’s research spans the 430 million-year history of sharks, as well as the vertebrate fossil and subfossil records throughout the Midwestern United States, looking at species as diverse as bobcats and rattlesnakes.

Gardner is a librarian at WVU Potomac State College in Keyser, West Virginia, and holds a bachelor’s degree in ecology and evolutionary biology from Marshall University as well as an associate in geology from Potomac State College.

Gardner teaches library instruction and provides reference assistance for students — in his spare time, he collaborates with other researchers on various scientific topics.

Looking to start a cool career related to shark conservation?

WVU Potomac State College offers 65+ majors, including animal science, biology, pre-veterinary medicine, and wildlife and fisheries resources.

Written by Nick Gardner/WVU Potomac State College.