Thanks to researchers in different fields who put in nearly two decades of past work on mRNA vaccine technology, people around the world are being immunized today from COVID-19—and hopefully leading us out of this pandemic.

Now, because of the increased focus on this versatile technology and that foundation of research, mRNA vaccines for other diseases have an even greater chance of making it to patients.

That includes cancer—which is just one of several areas outside of infectious diseases that researchers at Penn have been investigating.

Here’s a breakdown of how an mRNA-based vaccine could work to fight tumors, the challenges that need to be overcome, the technology’s roots in oncology, and where it’s headed.

The mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 protect people from the virus.

But a cancer mRNA vaccine is an intervention (a treatment) given to patients with the hope that their immune systems would be activated in a way that would attack tumor cells.

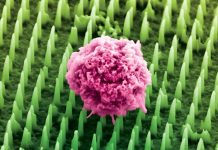

Through their research, the team found that mRNA vaccines can not only prompt strong antibody responses to fight off invaders, like COVID-19, but also potent cytotoxic T cell responses.

That’s important because these T cells can kill cancer cells. They just need to be altered or motivated to do it.

Think immunotherapy, like checkpoint inhibitors or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy that engineers a patient’s own T cells to find and destroy cancer cells.

The biggest challenge in developing these types of mRNA vaccines for cancer, though, is just how personal it has to be. The majority of everyone’s tumor neoantigens are specific to them.

It can’t be a catch-all approach like other vaccines—it needs to be personalized, much like CAR T cell therapy, which requires taking a patient’s own T cells, engineering them to seek out a specific antigen on a tumor cell, and then infusing them back in to find and kill them.

A similar vaccine for metastatic prostate cancer known as sipuleucel-T (Provenge) stimulates an immune response to prostatic acid phosphatase, or PAP, an antigen present on most prostate cancers.

While it’s not mRNA technology, it is customized for each patient and been shown in clinical trials to increase the survival of men with hormone refractory metastatic prostate cancer by about four months.

So far, it’s the only one approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

It wasn’t just years of virology and immunology studies that led us to the COVID-19 vaccines. Cancer research also played an important role.

In fact, the mRNA vaccine platform from BioNTech was first developed and tested in humans initially as an experimental cancer vaccine as far back as 2008, when 13 melanoma patients were vaccinated using the mRNA platform.

When they were vaccinated, the immune system’s reactivity against tumors did become elevated, the researchers reported. And as a result, their risk of developing new metastatic lesions was significantly reduced.

Moderna’s cancer mRNA vaccine, which takes a different approach, similarly induced an immune response in solid tumors—work that also began years ago.

And when they combined it with a checkpoint inhibitor, the therapy shrank tumors in six out of 20 patients.

A more recent preclinical study also showed how an RNA vaccine platform could be used in combination with CAR-T cell therapy to bolster it when there is weaker stimulation and responses.

The so-called “CARVac” approach activates dendritic cells, which in turn stimulates and enhances the efficacy of CAR-T cells, the researchers reported in Science last year.

Written by Steve Graff.

If you care about cancer, please read studies about this common beverage linked to lower prostate cancer risk and findings of this drug for depression may help stop cancer growth.

For more information about cancer and your health, please see recent studies about aspirin may boost survival in these two cancers and results showing that this drug can strengthen immune system to fight cancer.

The study is published in Clinical Cancer Research. One author of the study is Norbert Pardi.