Planning ahead is something astronomy and space exploration excels at.

Decadal surveys and years of engineering effort for missions give the field a much longer time horizon than many others.

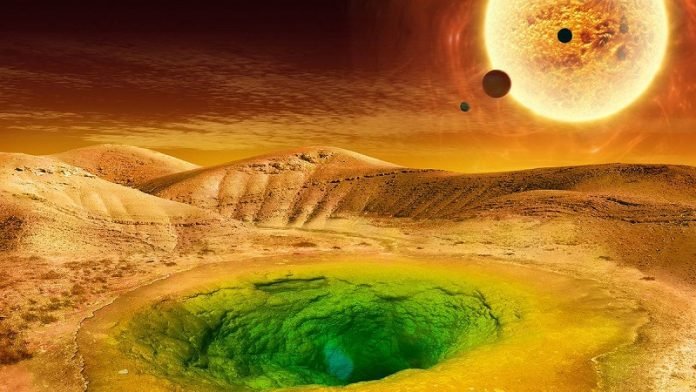

In the near future, scientists know there will be plenty of opportunities to search for biosignatures everywhere from nearby ocean worlds (i.e. Titan) to far away potentially habitable exoplanets.

But it’s not clear what those biosignatures would look like.

After all, currently there is only Earth’s biosphere to study, and it would be unfortunate to miss hints of another just because it didn’t look like those found on Earth.

Now a team led by researchers at the Santa Fe Institute (SFI) have come up with a framework that could help scientists look for biosignatures that might be completely different from those found on Earth.

That framework relies on stoichiometry. A common feature of high school chemistry classes, stoichiometry is the study of chemical ratios.

There are some obvious stoichiometric ratios on Earth that are clearly formed by life as we know it. Generalizing those ratios to be applicable anywhere was the focus of the paper from SFI.

There were three main principles that collectively make up the new framework.

The first principle is that stoichiometric values change with the cell size of individual cells. For example, as bacteria grow bigger the concentration of RNA increases while the concentration of individual proteins decreases.

When those cells die, their size would help to determine what concentration of molecules are released into the environment.

Environmental distribution is also impacted by the second principle – that the number of cells in an environment follows a power law distribution in relation to their size.

For example, there are most likely many more small cells than there are large ones, according to the simplest power law distribution curve. This size ratio, along with the stoichiometries associated with those different sizes then led to the third principle.

Applying that stoichiometric principle one step further leads to a result that can be applied to biospheres more generally. In this case, the size of a given particle is a determining factor of its ratio with the fluid that it is surrounded by.

Let’s continue using RNA and proteins as an example. RNA is an order of magnitude bigger than a protein.

It is also more prevalent in larger cells, according to the first principle. Larger cells, however, are less prevalent in the environment, according to the second principle.

Therefore, in a biologically active system, proteins, which are smaller, are more likely to have a higher concentration in a surrounding fluid than RNA, which is larger, would. Hence, the third principle that its size determines a particle’s concentration in a surrounding liquid.

The immediate application of this framework is studying ocean worlds, like Titan or Enceladus, where there are likely liquid bodies that could have concentrations of biological molecules inside of them.

Unfortunately, for now, there are no systems that can accurately measure particle size that could launch on any missions to these worlds.

But that doesn’t mean there won’t be in the future. So the potential for using this framework now requires a bit more engineering expertise to develop such a system. And it’s already clear how good the astronomy and space exploration community are at that.

Written by Andy Tomaswick.

Source: Universe Today.