Scientist have designed a new ultra-thin material that they have used to create elusive quantum states.

Called one-dimensional Majorana zero energy modes, these quantum states could have a huge impact for quantum computing.

At the core of a quantum computer is a qubit, which is used to make high-speed calculations.

The qubits that Google, for example, in its Sycamore processor unveiled last year, and others are currently using are very sensitive to noise and interference from the computer’s surroundings, which introduces errors into the calculations.

A new type of qubit, called a topological qubit, could solve this issue, and 1D Majorana zero energy modes may be the key to making them.

‘A topological quantum computer is based on topological qubits, which are supposed to be much more noise tolerant than other qubits.

However, topological qubits have not been produced in the lab yet,’ explains Professor Peter Liljeroth, the lead researcher on the project.

What are MZMs?

MZMs are groups of electrons bound together in a specific way so they behave like a particle called a Majorana fermion, a semi-mythical particle first proposed by semi-mythical physicist Ettore Majorana in the 1930s.

If Majorana’s theoretical particles could be bound together, they would work as a topological qubit.

One catch: no evidence for their existence has ever been seen, either in the lab or in astronomy.

Instead of attempting to make a particle that no one has ever seen anywhere in the universe, researchers instead try to make regular electrons behave like them.

To make MZMs, researchers need incredibly small materials, an area in which Professor Liljeroth’s group at Aalto University specialises.

MZMs are formed by giving a group of electrons a very specific amount of energy, and then trapping them together so they can’t escape.

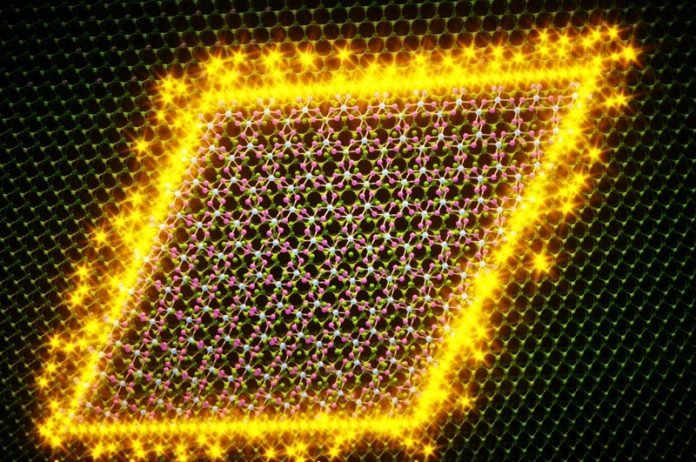

To achieve this, the materials need to be 2-dimensional, and as thin as physically possible. To create 1D MZMs, the team needed to make an entirely new type of 2D material: a topological superconductor.

Topological superconductivity is the property that occurs at the boundary of a magnetic electrical insulator and a superconductor.

To create 1D MZMs, Professor Liljeroth’s team needed to be able to trap electrons together in a topological superconductor, however it’s not as simple as sticking any magnet to any superconductor.

‘If you put most magnets on top of a superconductor, you stop it from being a superconductor,’ explains Dr. Shawulienu Kezilebieke, the first author of the study.

‘The interactions between the materials disrupt their properties, but to make MZMs, you need the materials to interact just a little bit.

The trick is to use 2D materials: they interact with each other just enough to make the properties you need for MZMs, but not so much that they disrupt each other.’

The property in question is the spin. In a magnetic material, the spin is aligned all in the same direction, whereas in a superconductor the spin is anti-aligned with alternating directions.

Bringing a magnet and a superconductor together usually destroys the alignment and anti-alignment of the spins.

However, in 2D layered materials the interactions between the materials are just enough to “tilt” the spins of the atoms enough that they create the specific spin state, called Rashba spin-orbit coupling, needed to make the MZMs.

Finding the MZMs

The topological superconductor in this study is made of a layer of chromium bromide, a material which is still magnetic when only one-atom-thick.

Professor Liljeroth’s team grew one-atom-thick islands of chromium bromide on top of a superconducting crystal of niobium diselenide, and measured their electrical properties using a scanning tunneling microscope.

At this point, they turned to the computer modelling expertise of Professor Adam Foster at Aalto University and Professor Teemu Ojanen, now at Tampere University, to understand what they had made.

‘There was a lot of simulation work needed to prove that the signal we’re seeing was caused by MZMs, and not other effects,’ says Professor Foster. ‘We needed to show that all the pieces fitted together to prove that we had produced MZMs.’

Now the team is sure that they can make 1D MZMs in 2-dimensional materials, the next step will be to attempt to make them into topological qubits.

This step has so far eluded teams who have already made 0-dimensional MZMs, and the Aalto team are unwilling to speculate on if the process will be any easier with 1-dimensional MZMs, however they are optimistic about the future of 1D MZMs.

‘The cool part of this paper is that we’ve made MZMs in 2D materials,’ said Professor Liljeroth ‘In principle these are easier to make and easier to customise the properties of, and ultimately make into a usable device.’

The study has been published in Nature.