Researchers have developed an ultrathin pressure sensor that can be attached directly to the skin.

It can measure how fingers interact with objects to produce useful data for medical and technological applications.

The sensor has minimal effect on the users’ sensitivity and ability to grip objects, and it is resistant to disruption from rubbing.

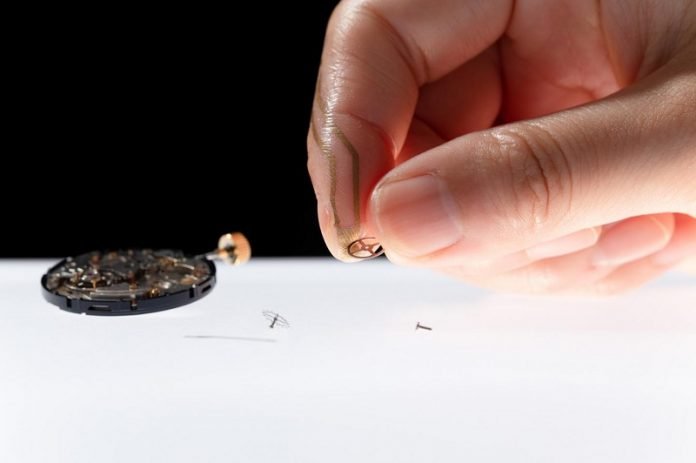

The team also hopes their sensor can be used for the novel task of digitally archiving the skills of craft workers.

There are many reasons why researchers wish to record motion and other physical details associated with hands and fingers.

Our hands are our primary tools for directly interacting with, and manipulating, materials and our immediate environments.

By recording the way in which hands perform various tasks, it could help researchers in fields such as sports and medical science, as well as neuroengineering and more. But capturing this data is not easy.

“Our fingertips are extremely sensitive, so sensitive in fact that a superthin plastic foil just a few millionths of a meter thick is enough to affect somebody’s sensations,” said Lecturer Sunghoon Lee of the Someya Group at the University of Tokyo.

“So a wearable sensor for your fingers has to be extremely thin. But this obviously makes it very fragile and susceptible to damage from rubbing or repeated physical actions. In order to overcome this, we created a special functional material that is thin and porous called a nanomesh sensor.”

Lee and his team made two kinds of layers for their sensors. Both layers were made by a process called electro spinning, which resembles a spider spinning its web.

One is an insulating polyurethane mesh with fibers about 200 nanometers to 400 nanometers thick, about one-five-hundredth the thickness of human hair.

The second layer is a stencil-like network of lines that forms the functional electronic component of the sensor.

This is made from gold and uses a supporting frame of polyvinyl alcohol, often found in contact lenses, which after manufacture is washed away to leave only the gold traces it was supporting. Multiple layers combine to form a functional pressure and movement sensor.

“We performed a rigorous set of tests on our sensors with the help of 18 test subjects,” said Lee. “They confirmed that the sensors were imperceptible and affected neither the ability to grip objects through friction, nor the perceived sensitivity compared to performing the same task without a sensor attached.

This is exactly the result we were hoping for.”

This is the first time in the world a fingertip-mounted sensor with no effect on skin sensitivity has been successfully demonstrated.

And the sensor maintained its performance as a pressure sensor even after being rubbed against a surface with a force of 100 kilopascals, roughly equivalent to atmospheric pressure, 300 times without breaking.

A novel application the team would like to see is the digital archiving of delicate craftwork by artisans or even the work of highly skilled surgeons.

If these processes can be recorded, it could become possible to train machines in how to perform tasks to a greater degree of fidelity than has ever been achieved before.