Throughout the pandemic, infectious disease experts and frontline medical workers have asked for a faster, cheaper and more reliable COVID-19 test.

In a new study, researchers created a highly automated device that can identify the presence of the novel coronavirus in just a half-hour.

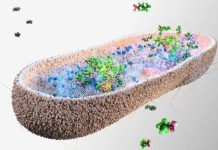

They leveraged the so-called “lab on a chip” technology and the cutting-edge genetic editing technique known as CRISPR.

The microlab is a microfluidic chip just half the size of a credit card containing a complex network of channels smaller than the width of a human hair.

The research was conducted by a team at Stanford.

The microlab test takes advantage of the fact that coronaviruses like SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, leaves behind tiny genetic fingerprints wherever they go in the form of strands of RNA, the genetic precursor of DNA.

If the coronavirus’s RNA is present in a swab sample, the person from whom the sample was taken is infected.

To initiate a test, liquid from a nasal swab sample is dropped into the microlab, which uses electric fields to extract and purify any nucleic acids like RNA that it might contain.

The purified RNA is then converted into DNA and then replicated many times over using a technique known as isothermal amplification.

Next, the team used an enzyme called CRISPR-Cas12 to determine if any of the amplified DNA came from the coronavirus.

If so, the activated enzyme triggers fluorescent probes that cause the sample to glow.

Here also, electric fields play a crucial role by helping concentrate all of the important ingredients—the target DNA, the CRISPR enzyme, and the fluorescent probes—together into a tiny space smaller than the width of a human hair, dramatically increasing the chances they will interact.

Several human-scale diagnostic tests use similar gene amplification and enzyme techniques, but they are slower and more expensive than the new test, which provides results in just 30 minutes.

Other tests can require more manual steps and can take several hours.

The researchers say their approach is not specific to COVID-19 and could be adapted to detect the presence of other harmful microbes, such as E. coli in food or water samples, or tuberculosis and other diseases in the blood.

One author of the study is Juan G. Santiago, the Charles Lee Powell Foundation Professor of mechanical engineering.

The study is published in PNAS.

Copyright © 2020 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.