Venus might not be a sweltering, waterless hellscape today, if Jupiter hadn’t altered its orbit around the sun, according to new UC Riverside research.

Jupiter has a mass that is two-and-a-half times that of all other planets in our solar system — combined.

Because it is comparatively gigantic, it has the ability to disturb other planets’ orbits.

Early in Jupiter’s formation as a planet, it moved closer to and then away from the sun due to interactions with the disc from which planets form as well as the other giant planets. This movement in turn affected Venus.

Observations of other planetary systems have shown that similar giant planet migrations soon after formation may be a relatively common occurrence. These are among the findings of a new study published in the Planetary Science Journal.

Scientists consider planets lacking liquid water to be incapable of hosting life as we know it.

Though Venus may have lost some water early on for other reasons, and may have continued to do so anyway, UCR astrobiologist Stephen Kane said that Jupiter’s movement likely triggered Venus onto a path toward its current, inhospitable state.

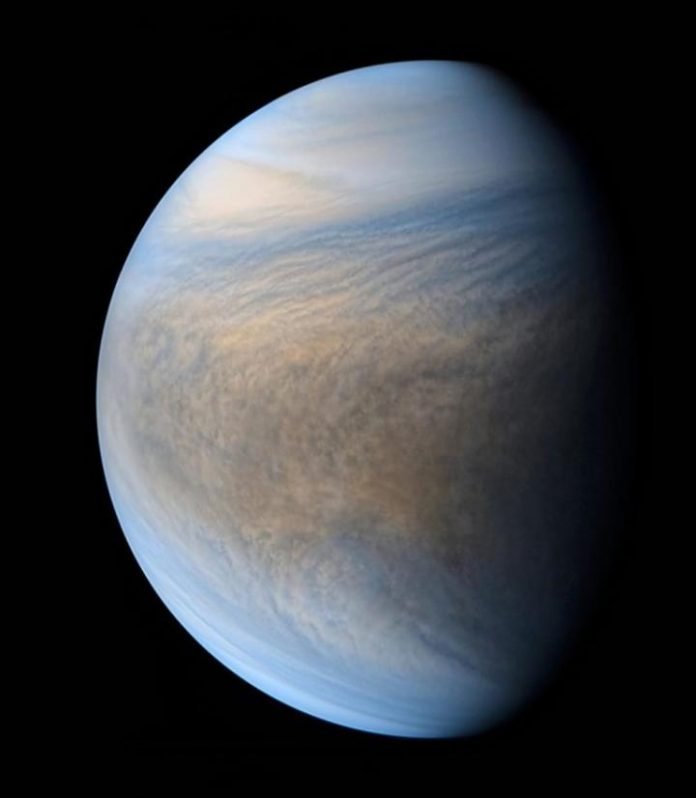

“One of the interesting things about the Venus of today is that its orbit is almost perfectly circular,” said Kane, who led the study.

“With this project, I wanted to explore whether the orbit has always been circular and if not, what are the implications of that?”

To answer these questions, Kane created a model that simulated the solar system, calculating the location of all the planets at any one time and how they pull one another in different directions.

Scientists measure how noncircular a planet’s orbit is between 0, which is completely circular, and 1, which is not circular at all. The number between 0 and 1 is called the eccentricity of the orbit. An orbit with an eccentricity of 1 would not even complete an orbit around a star; it would simply launch into space, Kane said.

Currently, the orbit of Venus is measured at 0.006, which is the most circular of any planet in our solar system. However, Kane’s model shows that when Jupiter was likely closer to the sun about a billion years ago, Venus likely had an eccentricity of 0.3, and there is a much higher probability that it was habitable then.

“As Jupiter migrated, Venus would have gone through dramatic changes in climate, heating up then cooling off and increasingly losing its water into the atmosphere,” Kane said.

Recently, scientists generated much excitement by discovering a gas in the clouds above Venus that may indicate the presence of life. The gas, phosphine, is typically produced by microbes, and Kane says it is possible that the gas represents “the last surviving species on a planet that went through a dramatic change in its environment.”

For that to be the case, however, Kane notes the microbes would have had to sustain their presence in the sulfuric acid clouds above Venus for roughly a billion years since Venus last had surface liquid water — a difficult to imagine though not impossible scenario.

“There are probably a lot of other processes that could produce the gas that haven’t yet been explored,” Kane said.

Ultimately, Kane says it is important to understand what happened to Venus, a planet that was once likely habitable and now has surface temperatures of up to 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

“I focus on the differences between Venus and Earth, and what went wrong for Venus, so we can gain insight into how the Earth is habitable, and what we can do to shepherd this planet as best we can,” Kane said.

Written by Jules Bernstein.