Researchers have designed a skin-like device that can measure small facial movements in patients who have lost the ability to speak.

People with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) suffer from a gradual decline in their ability to control their muscles.

As a result, they often lose the ability to speak, making it difficult to communicate with others.

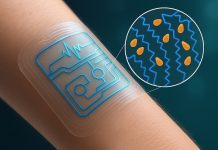

A team of MIT researchers has now designed a stretchable, skin-like device that can be attached to a patient’s face and can measure small movements such as a twitch or a smile.

Using this approach, patients could communicate a variety of sentiments, such as “I love you” or “I’m hungry,” with small movements that are measured and interpreted by the device.

The researchers hope that their new device would allow patients to communicate in a more natural way, without having to deal with bulky equipment.

The wearable sensor is thin and can be camouflaged with makeup to match any skin tone, making it unobtrusive.

“Not only are our devices malleable, soft, disposable, and light, they’re also visually invisible,” says Canan Dagdeviren, the LG Electronics Career Development Assistant Professor of Media Arts and Sciences at MIT and the leader of the research team.

“You can camouflage it and nobody would think that you have something on your skin.”

The researchers tested the initial version of their device in two ALS patients (one female and one male, for gender balance) and showed that it could accurately distinguish three different facial expressions — smile, open mouth, and pursed lips.

MIT graduate student Farita Tasnim and former research scientist Tao Sun are the lead authors of the study, which appears today in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Other MIT authors are undergraduate Rachel McIntosh, postdoc Dana Solav, research scientist Lin Zhang, and senior lab manager David Sadat. Yuandong Gu of the A*STAR Institute of Microelectronics in Singapore and Nikta Amiri, Mostafa Tavakkoli Anbarani, and M. Amin Karami of the University of Buffalo are also authors.

A skin-like sensor

Dagdeviren’s lab, the Conformable Decoders group, specializes in developing conformable (flexible and stretchable) electronic devices that can adhere to the body for a variety of medical applications.

She became interested in working on ways to help patients with neuromuscular disorders communicate after meeting Stephen Hawking in 2016, when the world-renowned physicist visited Harvard University and Dagdeviren was a junior fellow in Harvard’s Society of Fellows.

Hawking, who passed away in 2018, suffered from a slow-progressing form of ALS. He was able to communicate using an infrared sensor that could detect twitches of his cheek, which moved a cursor across rows and columns of letters.

While effective, this process could be time-consuming and required bulky equipment.

Other ALS patients use similar devices that measure the electrical activity of the nerves that control the facial muscles. However, this approach also requires cumbersome equipment, and it is not always accurate.

“These devices are very hard, planar, and boxy, and reliability is a big issue. You may not get consistent results, even from the same patients within the same day,” Dagdeviren says.

Most ALS patients also eventually lose the ability to control their limbs, so typing is not a viable strategy to help them communicate. The MIT team set out to design a wearable interface that patients could use to communicate in a more natural way, without the bulky equipment required by current technologies.

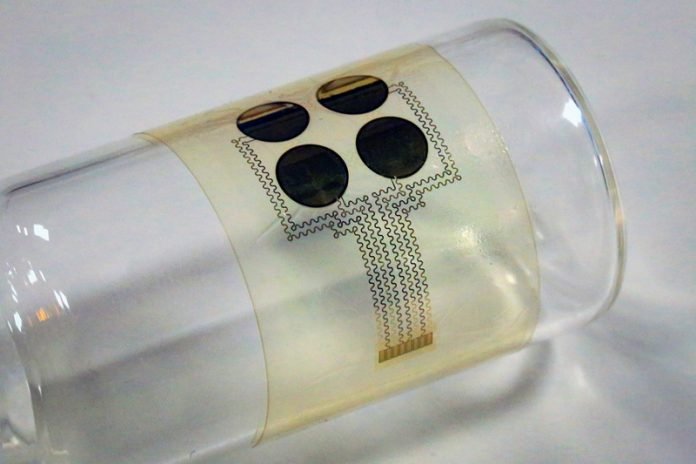

The device they created consists of four piezoelectric sensors embedded in a thin silicone film. The sensors, which are made of aluminum nitride, can detect mechanical deformation of the skin and convert it into an electric voltage that can be easily measured. All of these components are easy to mass-produce, so the researchers estimate that each device would cost around $10.

The researchers used a process called digital imaging correlation on healthy volunteers to help them select the most useful locations to place the sensor.

They painted a random black-and-white speckle pattern on the face and then took many images of the area with multiple cameras as the subjects performed facial motions such as smiling, twitching the cheek, or mouthing the shape of certain letters.

The images were processed by software that analyzes how the small dots move in relation to each other, to determine the amount of strain experienced in a single area.

“We had subjects doing different motions, and we created strain maps of each part of the face,” McIntosh says.

“Then we looked at our strain maps and determined where on the face we were seeing a correct strain level for our device, and determined that that was an appropriate place to put the device for our trials.”

The researchers also used the measurements of skin deformations to train a machine-learning algorithm to distinguish between a smile, open mouth, and pursed lips.

Using this algorithm, they tested the devices with two ALS patients, and were able to achieve about 75 percent accuracy in distinguishing between these different movements. The accuracy rate in healthy subjects was 87 percent.

“The continuous monitoring of facial motions plays a key role in nonverbal communications for patients with neuromuscular disorders. Currently, the mainstream approach is camera tracking, which presents a challenge for continuous, portable usage,” says Takao Someya, a professor of electrical engineering and information systems and dean of the School of Engineering at the University of Tokyo, who was not involved in the study.

“The authors have successfully developed thin, wearable, piezoelectric sensors that can reliably decode facial strains and predict facial kinematics.”

Enhanced communication

Based on these detectable facial movements, a library of phrases or words could be created to correspond to different combinations of movements, the researchers say.

“We can create customizable messages based on the movements that you can do,” Dagdeviren says.

“You can technically create thousands of messages that right now no other technology is available to do. It all depends on your library configuration, which can be designed for a particular patient or group of patients.”

The information from the sensor is sent to a handheld processing unit, which analyzes it using the algorithm that the researchers trained to distinguish between facial movements.

In the current prototype, this unit is wired to the sensor, but the connection could also be made wireless for easier use, the researchers say.

The researchers have filed for a patent on this technology and they now plan to test it with additional patients. In addition to helping patients communicate, the device could also be used to track the progression of a patient’s disease, or to measure whether treatments they are receiving are having any effect, the researchers say.

“There are a lot of clinical trials that are testing whether or not a particular treatment is effective for reversing ALS,” Tasnim says. “Instead of just relying on the patients to report that they feel better or they feel stronger, this device could give a quantitative measure to track the effectiveness.”

The research was funded by the MIT Media Lab Consortium, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

Written by Anne Trafton.