If you get too close to a pufferfish, this undersea creature will blow up like a balloon to scare you away.

Now, a team of engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder has designed a robot that can do much the same thing—and it could make flying drones safer in the not-so-distant future.

PufferBot is the brainchild of graduate student Hooman Hedayati and his colleagues at the ATLAS Institute at CU Boulder.

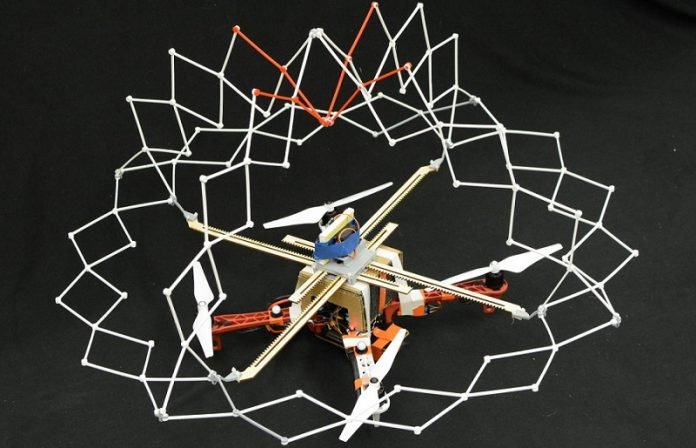

It’s a skittish machine: This hovering quadcopter drone comes complete with a plastic shield that can expand in size at a moment’s notice—forming a robotic airbag that could prevent dangerous collisions between people and machines.

The researchers presented their results virtually at the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2020).

Think of it like introducing a bit of coral reef to the world of high-tech robotics.

“We were trying to design a safer robot that could communicate safety information to the user,” Hedayati said. “We started by looking at how animals do the same thing.”

Drones, he explained, are becoming a more ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, taking on tasks from inspecting bridges for cracks to delivering packages to your doorstep. But as these machines proliferate in homes and workplaces, safety will be more important than ever.

“I’ve been working with drones for years, but whenever I go out and fly robots, I still feel not confident,” Hedayati said. “What happens if it falls on someone and hurts them? Technologies like PufferBot can help.”

CU Boulder team members on the project include Daniel Leithinger and Daniel Szafir, both assistant professors in ATLAS and the Department of Computer Science, and Ryo Suzuki, a former graduate student now at the University of Calgary.

Epic fails

Those kinds of accidents aren’t just a future problem.

Just check out YouTube where videos of drone “fails,” from spectacular crashes to collisions with humans, abound. Those kinds of dangers, Hedayati said, could make many people (justifiably) wary about inviting robots into their homes.

“We’ve been told that robots are great and can do a lot of tasks,” he said. “But where are these robots? Why are they not in our houses? Why do you see them inside cages in factories?”

It’s that safety-first mindset that forms the bulk of the engineer’s research.

Hedayati and his colleagues have previously experimented with using augmented reality (AR) tools to keep humans and robots from bumping into each other as they work side-by-side. Humans can don AR goggles, for example, to track the flight paths of drones in their vicinity. In one case, the team communicated that information to users by making the drone look like what Hedayati called “a giant, creepy eyeball.”

But what happens if those kinds of tools don’t work? Enter PufferBot, the robot inspired by some of nature’s weirdest fish.

“Imagine someone is walking closer to a robot, and there’s no way for it to escape,” Hedayati said.

Search and rescue

In practice, PufferBot looks less like a fish and more like a Hoberman sphere, one of those expandable plastic balls that you can find at many toy stores. The robot’s “airbag” is made out of hoops of plastic that are fastened to its top and can inflate from roughly 20 inches to 33 inches in diameter.

Under normal circumstances, the shield collapses and stays out of the way. But when danger is close, that’s when PufferBot puffs up, extending those hoops over its four, spinning rotors to keep them away from people and obstacles.

“It can act as a temporary cage,” Hedayati said. “It also communicates with users to tell them: ‘Don’t come close to me.’”

The design works like a charm: The robot’s shield is able to sustain a wide range of potential collisions and weighs a little over a pound—light enough that it won’t impede PufferBot’s flying.

Hedayati has high hopes for his team’s invention. He imagines that, one day, a PufferBot-like robot could fly into a collapsed building to search for survivors, all while using its shield to avoid smashing into rubble.

As for real pufferfish—those you still want to avoid.

Written by Daniel Strain.