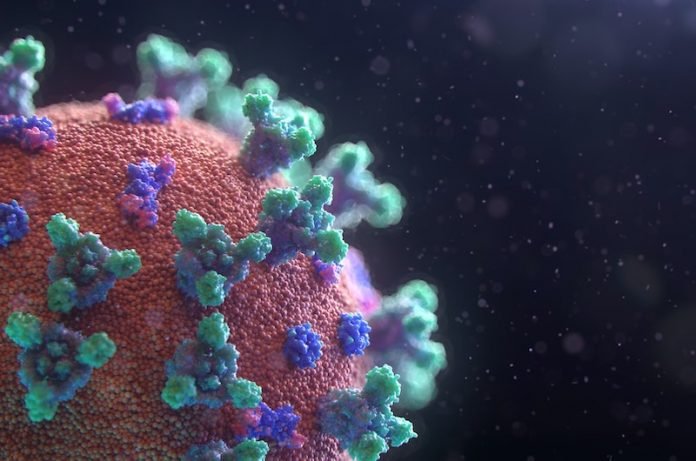

In a new study, researchers have found that natural infection with COVID-19 produces a robust T cell response, including inducing T cell ‘memory’ to potentially fight future infections.

The research was conducted by a team at Oxford University and elsewhere.

While research has shown that COVID-19 induces a B cell antibody response, it has been less clear whether COVID-19 causes the immune system to make virus-specific T cells too, and whether they are important for recovery from the initial infection, and protection against new infections.

While antibodies latch onto and destroy disease-causing agents like viruses and bacteria, T cells latch on to diseased cells within the body, such as tumor cells or virus-infected cells.

By studying the T cell immune response in depth and breadth, scientists can build a better understanding of why some people develop the milder disease, and how they might be able to prevent or treat infections.

T-cells also help attract other immune cells to the area. They may also be longer-lasting than antibodies, and so could offer alternative methods to diagnose whether someone has had a past COVID-19 infection after antibody levels have waned.

In this study, the researchers analyzed blood samples from COVID-19 patients to identify peptides containing T cell epitopes, including six immunodominant regions (epitope clusters) that were targeted by T cells in many of the patients.

They compared blood samples from 28 mild and 14 severely ill COVID-19 patients, as well as samples from 16 healthy donors.

They found that people with mild COVID-19 had a different pattern of T cell response when compared to those with more severe infection; this could help provide insights into the nature of immune protection.

While the research team thinks that a poor quality T cell response might contribute to SARS-CoV-2 viral persistence and COVID-19 mortality, recovered patients with mild as well as the severe disease still had T cell memory two months after infection.

Only a small number of T cells need to have a memory of the primary infection, and they can replicate to mount a robust immune response quickly.

The researchers also found that the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 was often recognized by T-cells from recovered patients, which adds support for the approaches used by many of the current vaccines in development, including the Oxford vaccine.

They additionally found that other parts of the virus, including its membrane and its nucleoprotein, also provoked a strong T cell immune response, potentially providing other vaccine targets too.

The team now plans to investigate how long T cell immune memory lasts and whether this might have implications for novel diagnostic tests and new treatments.

One author of the study is Professor Tao Dong from the MRC Human Immunology Unit.

The study is published in Nature Immunology.

Copyright © 2020 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.