In a new study, researchers found humans are not the only species facing a potential threat from SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The research was conducted by a team from the University of California, Davis and elsewhere.

The team used genomic analysis to compare the main cellular receptor for the virus in humans—angiotensin converting enzyme-2, or ACE2—in 410 different species of vertebrates, including birds, fish, amphibians, reptiles and mammals.

ACE2 is normally found on many different types of cells and tissues, including epithelial cells in the nose, mouth and lungs.

In humans, 25 amino acids of the ACE2 protein are important for the virus to bind and gain entry into cells.

The researchers used these 25 amino acid sequences of the ACE2 protein, and modeling of its predicted protein structure together with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, to evaluate how many of these amino acids are found in the ACE2 protein of the different species.

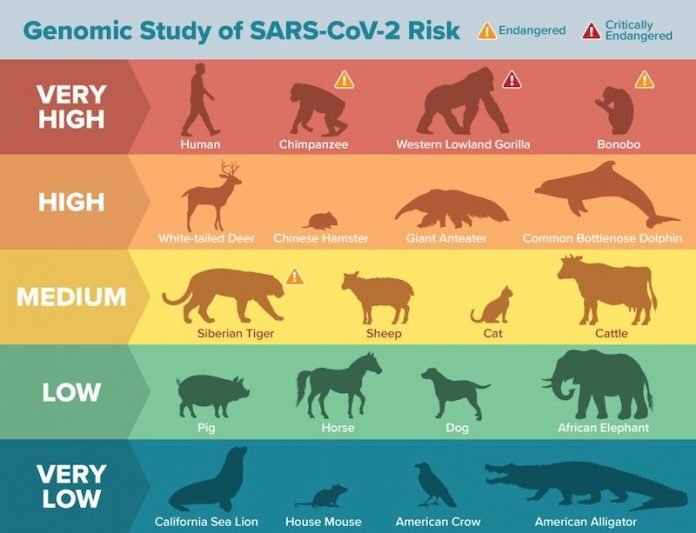

Animals with all 25 amino acid residues matching the human protein are predicted to be at the highest risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 via ACE2.

The risk is predicted to decrease the more the species’ ACE2 binding residues differ from humans.

About 40% of the species potentially susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 are classified as “threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and may be especially vulnerable to human-to-animal transmission.

The team found several critically endangered primate species, such as the Western lowland gorilla, Sumatran orangutan and Northern white-cheeked gibbon, are at very high risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 via their ACE2 receptor.

Other animals flagged as high risk include marine mammals such as gray whales and bottlenose dolphins, as well as Chinese hamsters.

Domestic animals such as cats, cattle and sheep were found to have a medium risk, and dogs, horses and pigs were found to have low risk for ACE2 binding.

How this relates to infection and disease risk needs to be determined by future studies, but for those species that have known infectivity data, the correlation is high.

In documented cases of SARS-COV-2 infection in mink, cats, dogs, hamsters, lions, and tigers, the virus may be using ACE2 receptors or they may use receptors other than ACE2 to gain access to host cells.

The lower propensity for binding could translate to lower propensity for infection, or the lower ability for the infection to spread in an animal or between animals once established.

Because of the potential for animals to contract the novel coronavirus from humans, and vice versa, institutions including the National Zoo and the San Diego Zoo, which both contributed genomic material to the study, have strengthened programs to protect both animals and humans.

The authors urge caution against over-interpreting the predicted animal risks based on the computational results, noting the actual risks can only be confirmed with additional experimental data.

One author of the study is Joana Damas, a postdoctoral research associate at UC Davis.

The study is published in PNAS.

Copyright © 2020 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.