Today’s brain implants already connect the nervous system to electronic devices to help people with spinal cord injuries regain some motor control.

But they use ungainly wires.

Stanford researchers have been working for years to advance a technology that could one day help people with paralysis regain use of their limbs, and enable amputees to use their thoughts to control prostheses and interact with computers.

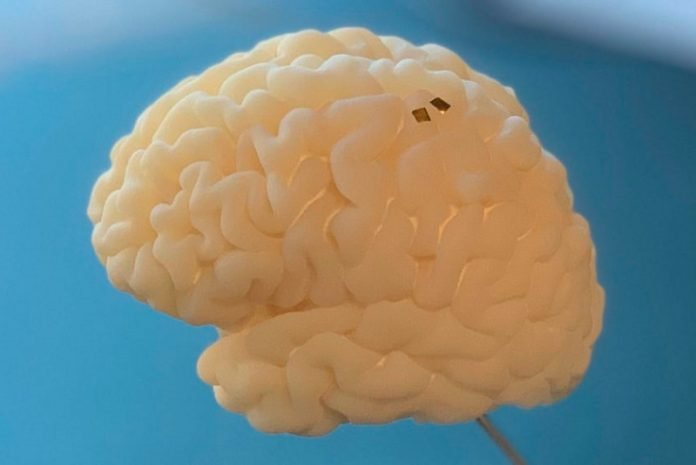

The team has been focusing on improving a brain-computer interface, a device implanted beneath the skull on the surface of a patient’s brain.

This implant connects the human nervous system to an electronic device that might, for instance, help restore some motor control to a person with a spinal cord injury, or someone with a neurological condition like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease.

The current generation of these devices record enormous amounts of neural activity, then transmit these brain signals through wires to a computer.

But when researchers have tried to create wireless brain-computer interfaces to do this, it took so much power to transmit the data that the devices would generate too much heat to be safe for the patient.

Now, a team led by electrical engineers and neuroscientists Krishna Shenoy, PhD, and Boris Murmann, PhD, and neurosurgeon and neuroscientist Jaimie Henderson, MD, have shown how it would be possible to create a wireless device, capable of gathering and transmitting accurate neural signals, but using a tenth of the power required by current wire-enabled systems.

These wireless devices would look more natural than the wired models and give patients freer range of motion.

Graduate student Nir Even-Chen and postdoctoral fellow Dante Muratore, PhD, describe the team’s approach in a Nature Biomedical Engineering paper.

The team’s neuroscientists identified the specific neural signals needed to control a prosthetic device, such as a robotic arm or a computer cursor.

The team’s electrical engineers then designed the circuitry that would enable a future, wireless brain-computer interface to process and transmit these these carefully identified and isolated signals, using less power and thus making it safe to implant the device on the surface of the brain.

To test their idea, the researchers collected neuronal data from three nonhuman primates and one human participant in a (BrainGate) clinical trial.

As the subjects performed movement tasks, such as positioning a cursor on a computer screen, the researchers took measurements.

The findings validated their hypothesis that a wireless interface could accurately control an individual’s motion by recording a subset of action-specific brain signals, rather than acting like the wired device and collecting brain signals in bulk.

The next step will be to build an implant based on this new approach and proceed through a series of tests toward the ultimate goal.

Written by Tom Abate.