Roboticists at the University of California San Diego have developed an affordable, easy to use a system to track the location of flexible surgical robots inside the human body.

The system performs as well as the current state of the art methods but is much less expensive.

Many current methods also require exposure to radiation, while this system does not.

The system was developed by Tania Morimoto, a professor of mechanical engineering at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego, and mechanical engineering Ph.D. student Connor Watson.

Their findings are published in the IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters.

“Continuum medical robots work really well in highly constrained environments inside the body,” Morimoto said.

“They’re inherently safer and more compliant than rigid tools.

But it becomes a lot harder to track their location and their shape inside the body. And so if we are able track them more easily that would be a great benefit both to patients and surgeons.”

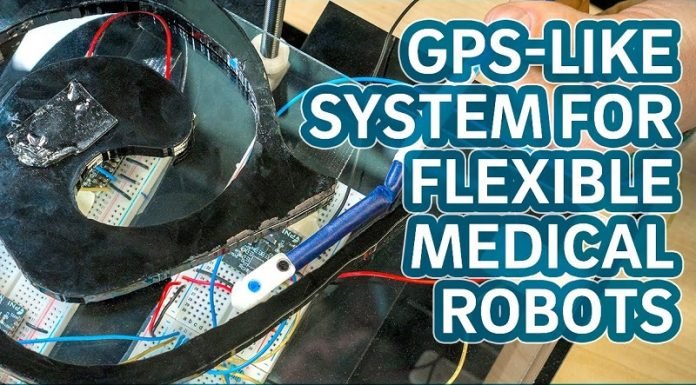

The researchers embedded a magnet in the tip of a flexible robot that can be used in delicate places inside the body, such as arterial passages in the brain.

“We worked with a growing robot, which is a robot made of very thin nylon that we invert, almost like a sock, and pressurize with a fluid which causes the robot to grow,” Watson said.

Because the robot is soft and moves by growing, it has very little impact on its surroundings, making it ideal for use in medical settings.

The researchers then used existing magnet localization methods, which work very much like GPS, to develop a computer model that predicts the robot’s location.

GPS satellites ping smartphones and based on how long it takes for the signal to arrive, the GPS receiver in the smartphone can determine where the cell phone is.

Similarly, researchers know how strong the magnetic field should be around the magnet embedded in the robot.

They rely on four sensors that are carefully spaced around the area where the robot operates to measure the magnetic field strength. Based on how strong the field is, they are able to determine where the tip of the robot is.

The whole system, including the robot, magnets, and magnet localization setup, costs around $100.

Morimoto and Watson went a step further. They then trained a neural network to learn the difference between what the sensors were reading and what the model said the sensors should be reading. As a result, they improved localization accuracy to track the tip of the robot.

“Ideally we are hoping that our localization tools can help improve these kinds of growing robot technologies. We want to push this research forward so that we can test our system in a clinical setting and eventually translate it into clinical use,” Morimoto said.