Soft and flexible materials called halide perovskites could make solar cells more efficient at significantly less cost, but they’re too unstable to use.

A Purdue University-led research team has found a way to make halide perovskites stable enough by inhibiting the ion movement that makes them rapidly degrade, unlocking their use for solar panels as well as electronic devices.

The discovery also means that halide perovskites can stack together to form heterostructures that would allow a device to perform more functions.

The results published in the journal Nature on Wednesday (April 29).

Other collaborating universities include Shanghai Tech University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of California, Berkeley, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Researchers already have seen that solar cells made out of perovskites in the lab perform just as well as the solar cells on the market made of silicon.

Perovskites have the potential to be even more efficient than silicon because less energy is wasted when converting solar energy to electricity.

And because perovskites can be processed from a solution into a thin film, like ink printed on paper, they could be more cheaply produced in higher quantities compared to silicon.

“There have been 60 years of a concerted effort making good silicon devices.

There may have been only 10 years of concerted effort on perovskites and they’re already as good as silicon, but they don’t last,” said Letian Dou (lah-TEEN dough), a Purdue assistant professor of chemical engineering.

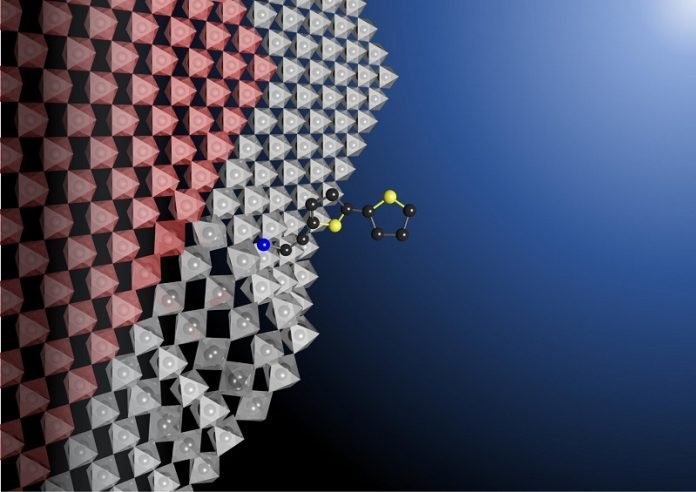

A perovskite is made up of components that an engineer can individually replace at the nanometer scale to tune the material’s properties. Including multiple perovskites in a solar cell or integrated circuit would allow the device to perform different functions, but perovskites are too unstable to stack together.

Dou’s team discovered that simply adding a rigid bulky molecule, called bithiophenylethylammonium, to the surface of a perovskite stabilizes the movement of ions, preventing chemical bonds from breaking easily.

The researchers also demonstrated that adding this molecule makes a perovskite stable enough to form clean atomic junctions with other perovskites, allowing them to stack and integrate.

“If an engineer wanted to combine the best parts about perovskite A with the best parts about perovskite B, that typically can’t happen because the perovskites would just mix together,” said Brett Savoie (SAHV-oy), a Purdue assistant professor of chemical engineering, who conducted simulations explaining what the experiments revealed on a chemical level.

“In this case, you really can get the best of A and B in a single material. That is completely unheard of.”

The bulky molecule allows a perovskite to stay stable even when heated to 100 degrees Celsius. Solar cells and electronic devices require elevated temperatures of 50-80 degrees Celsius to operate.

These findings also mean that it could be possible to incorporate perovskites into computer chips, the researchers said.

Tiny switches in computer chips, called transistors, rely on tiny junctions to control electrical current. A pattern of perovskites might allow the chip to perform more functions than with just one material.