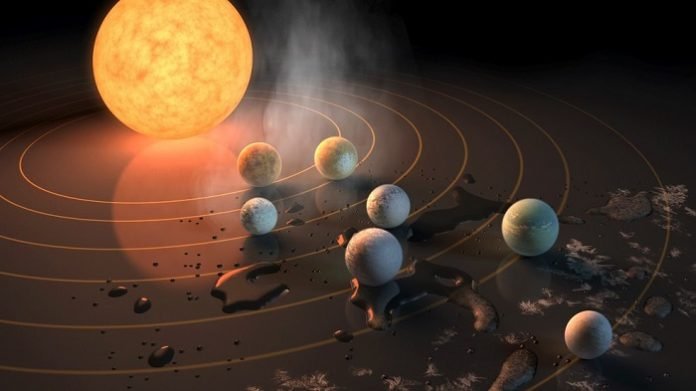

This month marks the third anniversary of the discovery of a remarkable system of seven planets known as TRAPPIST-1.

These rocky, Earth-size worlds orbit an ultra-cool star 39 light-years from Earth; 1 light-year is approximately 5.88 trillion miles.

Three of the planets are in the “habitable zone,” meaning they are at the right orbital distance to be warm enough for liquid water to exist on their surfaces.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will observe those worlds after its launch in 2021, with the goal of making the first detailed, near-infrared study of the atmosphere of a habitable-zone planet.

Numerous Cornell astronomy faculty will contribute to the mission. Nikole Lewis, assistant professor of astronomy and the deputy director of the Carl Sagan Institute, is the principal investigator for one of the teams investigating the TRAPPIST-1 system.

“It’s a coordinated effort because no one team could do everything we wanted to do with the TRAPPIST-1 system,” Lewis said. “The level of cooperation has been really spectacular.”

Lewis’ team will observe one of the planets, TRAPPIST-1e, in an effort to not only detect an atmosphere, but also to determine its basic composition.

They expect to be able to distinguish between an atmosphere dominated by water vapor and one composed mainly of nitrogen (like Earth) or carbon dioxide (like Mars and Venus).

TRAPPIST-1e is one of the known exoplanets having the most in common with Earth; its density and the amount of radiation that it receives from its star make it a great candidate for habitability.

Lewis will also lead 130 hours of guaranteed time observations focused on the detailed study of exoplanet atmospheres with Webb.

Ray Jayawardhana, the Harold Tanner Dean of Arts and Sciences and professor of astronomy, and Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy and director of the Carl Sagan Institute, are part of a team that will dedicate 200 hours of time on the Webb telescope to characterize exoplanets, including Trappist-1d (a hot, rocky, Venus-like planet) and Trappist-1f (a cooler, Earth-size planet).

“We look forward to ‘remote sensing’ a remarkable diversity of exoplanet atmospheres, ranging from temperate terrestrial worlds in the TRAPPIST-1 system to blazing gas giants orbiting very close to their stars,” Jayawardhana said.

“The Webb telescope will give us unprecedented views, especially of the smaller planets that are tougher to probe.”

Added Kaltenegger: “The combination of the data from the three TRAPPIST planets will give us unprecedented insight into how rocky planets evolve at different distances from their host star. It is the best laboratory that we could have asked for, to get insights into how extrasolar rocky planets work.”

Jonathan Lunine, David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences and chair of astronomy, is the interdisciplinary scientist for astrobiology on the Webb mission and serves on the Science Working Group, which defines the mission’s science requirements and provides scientific oversight of the project.

His hours on the telescope will be mostly used to look at “hot Jupiters” – gas giant planets that are very close to their stars – and Kuiper Belt objects.

James Lloyd, professor of astronomy, developed the Aperture Masking Interferometry mode of the telescope’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument, which will be used to image planetary systems and their environments.

The Webb telescope will be the world’s premier space science observatory, able to solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the enigmatic structures and origins of our universe.

Webb is an international program led by NASA, with partners the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency.

Written by Linda B. Glaser.