According to the most popular theory, proposed by Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, during a very early phase of the solar system’s formation, the giant planets scattered objects into the outer regions far away from the sun.

There, the icy rocks and dust particles formed a kind of cloud.

Passing stars may then scatter these objects back into the inner solar system, where we observe them as comets.

Coming from the Oort cloud, these long-period comets often take many more than 200 years to orbit the sun.

“We present a second potential origin for such comets,” says Tom Hands, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Computational Science of the University of Zurich.

“They can be captured out of interstellar space in the relatively recent past.”

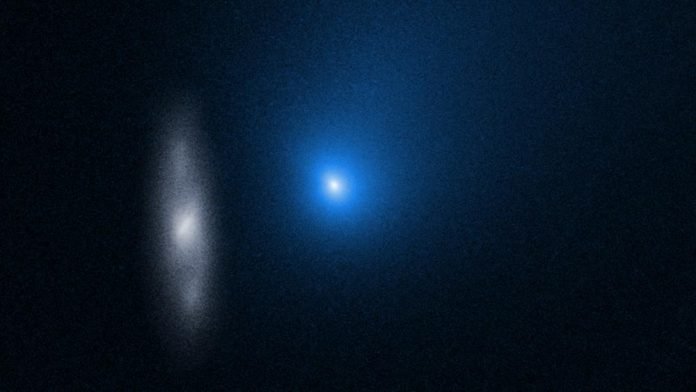

Two interstellar visitors made headlines in the past years. In 2017, scientists detected an asteroid-like body later named Oumuamua.

In August 2019, amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov discovered a comet that came from interstellar space and will leave the solar system again.

Oumuamua and Comet Borisov are both leftovers of planet formation in other solar systems, in the same way our comets and asteroids are thought to be the leftovers of planet formation in our solar system.

In the wake of the discovery of the first two interstellar objects, Hands and Walter Dehnen of the University of Munich used computer simulations to study how interstellar objects could be captured by our solar system.

“These stowaways form around distant stars before being flung towards us, making a journey of many lightyears before encountering Jupiter and being captured into the solar system,” explains Hands.

“We simulated 400 million such bodies as they approached the sun and Jupiter.”

The researchers used realistic velocities for these objects, based on data from the GAIA mission, and studied how they interact with Jupiter on their journey through the solar system. They did this work on the VESTA cluster of the University of Zurich.

“We used an advanced code which runs on graphics processing units rather than traditional computer processors to enable us to simulate such a large number of objects in a short time,” explains Hands.

“The simulations took two days in total using around 70 graphics cards, so roughly 140 days if we had only used one card and much, much longer if we had used a normal desktop computer processor.”

The results of the simulations, which appear in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveal that in a small minority of cases, Jupiter alters the trajectories of the objects enough that they become bound to the solar system.

“Although the capture probability is small, there could be anywhere from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of these alien comets orbiting the sun,” says the astrophysicist.

Captured objects are typically on orbits very similar to those of long-period comets that humanity has observed for centuries, suggesting that they are hiding in plain sight.

“If we could identify one, we would have a real possibility to study the composition of material formed in other Solar systems in close detail,” says Hands.

In an earlier paper from May 2019, Hands and colleagues studied how close interactions between stars in their birth cluster affect the comets and asteroids formed around each star.

They found that objects may become liberated and left “free-floating” in the galaxy, or alternatively “stolen” by other stars. This led them to suggest that the Oort cloud might be partially populated by objects that were formed around other stars but then captured by the sun in its birth cluster billions of years ago.

This latest study investigates the capture of free-floating asteroids and comets, which may have been liberated from their parent star by the mechanism demonstrated in the earlier study.