Chemists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have discovered a method that could turn plastic waste into valuable chemicals by using sunlight.

In lab experiments, the research team mixed plastics with their catalyst in a solvent, which allows the solution to harness light energy and convert the dissolved plastics into formic acid – a chemical used in fuel cells to produce electricity.

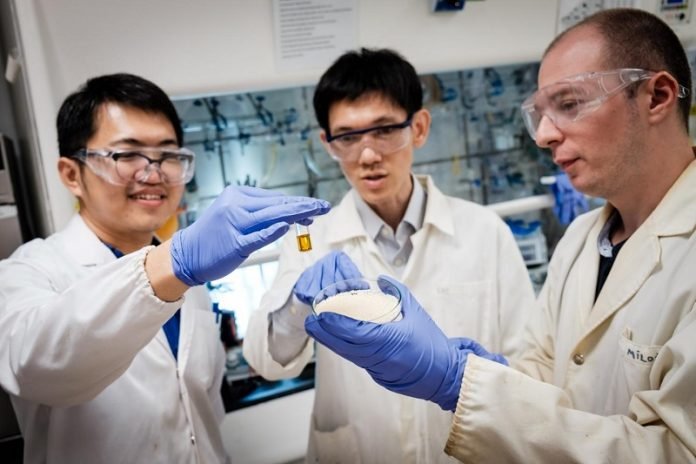

Reporting their work in Advanced Science, the team led by NTU Assistant Professor Soo Han Sen made their catalyst from the affordable, biocompatible metal vanadium, commonly used in steel alloys for vehicles and aluminium alloys for aircraft.

When the vanadium-based catalyst was dissolved in a solution containing a non-biodegradable consumer plastic like polyethylene and exposed to artificial sunlight, it broke down the carbon-carbon bonds within the plastic in six days.

This process turned the polyethylene into formic acid, a naturally occurring preservative and antibacterial agent, which can also be used for energy generation by power plants and in hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

“We aimed to develop sustainable and cost-effective methods to harness sunlight to manufacture fuels and other chemical products,” said Asst Prof Soo.

“This new chemical treatment is the first reported process that can completely break down a non-biodegradable plastic such as polyethylene using visible light and a catalyst that does not contain heavy metals.”

In Singapore, most plastic waste is incinerated, producing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, and the leftover mass – burn ash – is transported to the Semakau landfill, which is estimated to run out of space by 2035.

Developing innovative zero-waste solutions, such as this environmentally friendly catalyst to turn waste into resources, is part of the NTU Smart Campus vision to develop a sustainable future.

Using energy from the sun to convert chemicals

The vanadium-based catalyst, which is supported by organic groups and typically abbreviated as LV(O), uses light energy to drive a chemical reaction, and is known as a photocatalyst.

Photocatalysts enable chemical reactions to be powered by sunlight, unlike most reactions performed in industry that require heat, usually generated through the burning of fossil fuels.

Other advantages of the new photocatalyst are that it is low cost, abundant, and environmentally friendly, unlike common catalysts made from expensive or toxic metals such as platinum, palladium or ruthenium.

While scientists have tried other approaches for turning waste plastics into useful chemicals, many approaches involve undesirable reagents or too many steps to scale up.

One example is an approach called photoreforming, where plastic is combined with water and sunlight to produce hydrogen gas, but this requires the use of catalysts containing cadmium, a toxic heavy metal. Other methods require plastics to be treated with harsh chemical solutions that are dangerous to handle.

Most plastics are non-biodegradable because they contain extraordinarily inert chemical bonds called carbon-carbon bonds, which are not readily broken down without the application of high temperatures.

The new vanadium-based photocatalyst developed by the NTU research team was specially designed to break these bonds, and does so by latching onto a nearby chemical group known as an alcohol group and using energy absorbed from sunlight to unravel the molecule like a zipper.

As the experiments were conducted at laboratory scale, the plastic samples were first dissolved by heating to 85 degrees Celsius in a solvent, before the catalyst, which is in powder form, was dissolved.

The solution was then exposed to artificial sunlight for a few days.

Using this approach the team showed that their photocatalyst was able to break down the carbon-carbon bonds in over 30 different compounds and the results demonstrated the concept of an environmentally-friendly, low-cost photocatalyst.

The research team is now pursuing improvements to the process that may allow the breakdown of plastics to produce other useful chemical fuels, such as hydrogen gas.