Astronomers using ESO’s SPHERE instrument at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) have revealed that the asteroid Hygiea could be classified as a dwarf planet.

The object is the fourth largest in the asteroid belt after Ceres, Vesta and Pallas.

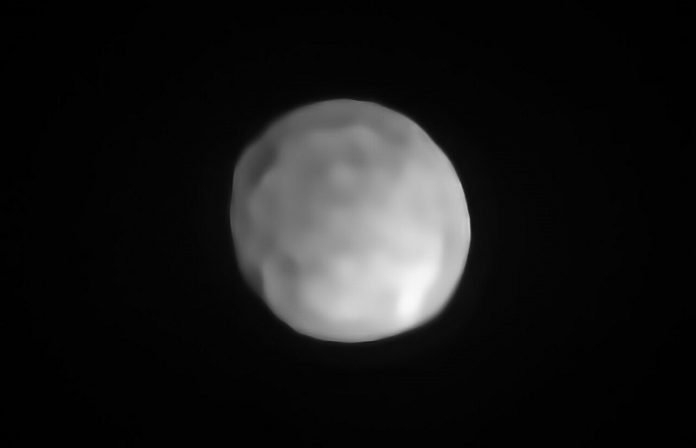

For the first time, astronomers have observed Hygiea in sufficiently high resolution to study its surface and determine its shape and size.

They found that Hygiea is spherical, potentially taking the crown from Ceres as the smallest dwarf planet in the Solar System.

As an object in the main asteroid belt, Hygiea satisfies right away three of the four requirements to be classified as a dwarf planet:

It orbits around the Sun, it is not a moon and, unlike a planet, it has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

The final requirement is that it has enough mass for its own gravity to pull it into a roughly spherical shape. This is what VLT observations have now revealed about Hygiea.

“Thanks to the unique capability of the SPHERE instrument on the VLT, which is one of the most powerful imaging systems in the world, we could resolve Hygiea’s shape, which turns out to be nearly spherical,” says lead researcher Pierre Vernazza from the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille in France.

“Thanks to these images, Hygiea may be reclassified as a dwarf planet, so far the smallest in the Solar System.”

The team also used the SPHERE observations to constrain Hygiea’s size, putting its diameter at just over 430 km. Pluto, the most famous of dwarf planets, has a diameter close to 2400 km, while Ceres is close to 950 km in size.

Surprisingly, the observations also revealed that Hygiea lacks the very large impact crater that scientists expected to see on its surface, the team report in the study published today in Nature Astronomy.

Hygiea is the main member of one of the largest asteroid families, with close to 7000 members that all originated from the same parent body. Astronomers expected the event that led to the formation of this numerous family to have left a large, deep mark on Hygiea.

“This result came as a real surprise as we were expecting the presence of a large impact basin, as is the case on Vesta,” says Vernazza. Although the astronomers observed Hygiea’s surface with a 95% coverage, they could only identify two unambiguous craters.

“Neither of these two craters could have been caused by the impact that originated the Hygiea family of asteroids whose volume is comparable to that of a 100 km-sized object. They are too small,” explains study co-author Miroslav Brož of the Astronomical Institute of Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic.

The team decided to investigate further. Using numerical simulations, they deduced that Hygiea’s spherical shape and large family of asteroids are likely the result of a major head-on collision with a large projectile of diameter between 75 and 150 km.

Their simulations show this violent impact, thought to have occurred about 2 billion years ago, completely shattered the parent body. Once the left-over pieces reassembled, they gave Hygiea its round shape and thousands of companion asteroids.

“Such a collision between two large bodies in the asteroid belt is unique in the last 3-4 billion years,” says Pavel Ševeček, a PhD student at the Astronomical Institute of Charles University who also participated in the study.

Studying asteroids in detail has been possible thanks not only to advances in numerical computation, but also to more powerful telescopes.

“Thanks to the VLT and the new generation adaptive-optics instrument SPHERE, we are now imaging main belt asteroids with unprecedented resolution, closing the gap between Earth-based and interplanetary mission observations,” Vernazza concludes.