Mars once had salt lakes similar to those on Earth and went through wet and dry periods, according to a new study.

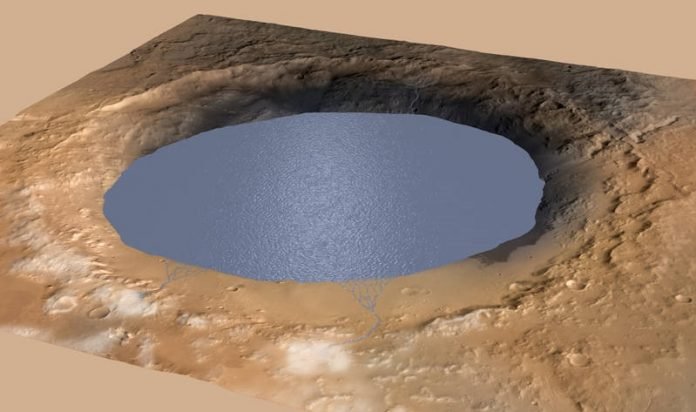

As reported in Nature Geoscience, researchers examined geological terrains on Mars from Gale Crater, an immense 95-mile-wide rocky basin that the NASA Curiosity rover has explored since 2012 as part of the MSL (Mars Science Laboratory) mission.

The results show that the lake that was present in Gale Crater over 3 billion years ago underwent a drying episode, potentially linked to the global drying of Mars.

Gale Crater formed about 3.6 billion years ago when a meteor hit Mars and created its large impact crater.

“Since then, its geological terrains have recorded the history of Mars, and studies have shown Gale Crater reveals signs that liquid water was present over its history, which is a key ingredient of microbial life as we know it,” says Marion Nachon, a postdoctoral research associate in the geology and geophysics department at Texas A&M University.

“During these drying periods, salt ponds eventually formed.

It is difficult to say exactly how large these ponds were, but the lake in Gale Crater was present for long periods of time—from at least hundreds of years to perhaps tens of thousands of years.”

Where did they go?

Nachon says Mars probably became drier over time, and the planet lost its planetary magnetic field, which left the atmosphere exposed and vulnerable to stripping from solar wind and radiation over millions of years.

“With an atmosphere becoming thinner, the pressure at the surface became lesser, and the conditions for liquid water to be stable at the surface were not fulfilled anymore,” Nachon says. “So liquid water became unsustainable and evaporated.”

Researchers believe salt ponds on Mars are similar to those found on Earth, especially those in a region called Altiplano, near the Bolivia-Peru border.

The Altiplano is an arid, high-altitude plateau where rivers and streams from mountain ranges “do not flow to the sea but lead to closed basins, similar to what used to happen at Gale Crater on Mars,” Nachon says.

“This hydrology creates lakes with water levels heavily influenced by climate. During the arid periods Altiplano lakes become shallow due to evaporation, and some even dry up entirely. The fact that the Atliplano is mostly vegetation-free makes the region look even more like Mars.”

Dried out climate

The study also shows that the ancient lake in Gale Crater underwent at least one episode of drying before “recovering.”

It’s also possible that the lake was segmented into separate ponds, where some could have undergone more evaporation.

Because up to now only one location along the rover’s path shows such a drying history, Nachon says it might give clues about how many drying episodes the lake underwent before Mars’s climate became as dry as it is today.

“It could indicate that Mars’s climate ‘dried out’ over the long term, on a way that still allowed for the cyclical presence of a lake,” Nachon says.

“These results indicate a past Mars climate that fluctuated between wetter and drier periods.

They also tell us about the types of chemical elements (in this case sulphur, a key ingredient for life) that were available in the liquid water present at the surface at the time, and about the type of environmental fluctuations Mars life would have had to cope with, if it ever existed.”

Written by Keith Randall.