Many patients, especially those who are anesthetized or emotionally challenged, cannot communicate precisely about their pain.

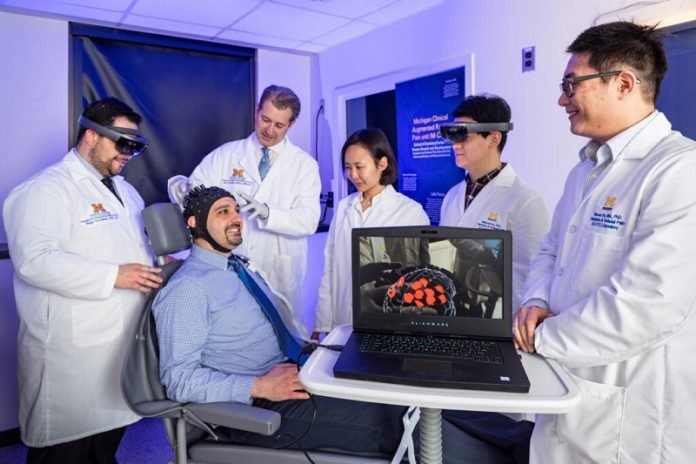

For this reason, University of Michigan researchers have developed a technology to help clinicians “see” and map patient pain in real-time, through special augmented reality glasses.

Their small feasibility study appears in the Journal of Medical Internet Research.

The technology was tested on 21 volunteer dental patients, and researchers hope to one day include other types of pain and conditions.

It’s years away from widespread use in a clinical setting, but the feasibility study is a good first step for dental patients, said Alex DaSilva, associate professor at the U-M School of Dentistry and director of the Headache and Orofacial Pain Effort Lab.

The portable CLARAi (clinical augmented reality and artificial intelligence) platform combines visualization with brain data using neuroimaging to navigate through a patient’s brain while they’re in the chair.

“It’s very hard for us to measure and express our pain, including its expectation and associated anxiety,” DaSilva said.

“Right now, we have a one to 10 rating system, but that’s far from a reliable and objective pain measurement.”

In the study, researchers triggered pain by administering cold to the teeth. Researchers used brain pain data to develop algorithms that, when coupled with new software and neuroimaging hardware, predicted pain or the absence of it about 70% of the time.

Participants wore a sensor-outfitted cap that detected changes to blood flow and oxygenation, thus measuring brain activity and responses to pain. That information was transmitted to a computer and interpreted.

Wearing special augmented reality glasses (in this case, the Microsoft HoloLens), researchers viewed the subject’s brain activity in real time on a reconstructed brain template, while the subjects sat in the clinical chair.

The red and blue dots on the image denote location and level of brain activity, and this “pain signature” was mirror-displayed on the augmented reality screen. The more pain signatures the algorithm learns to read, the more accurate the pain assessment.