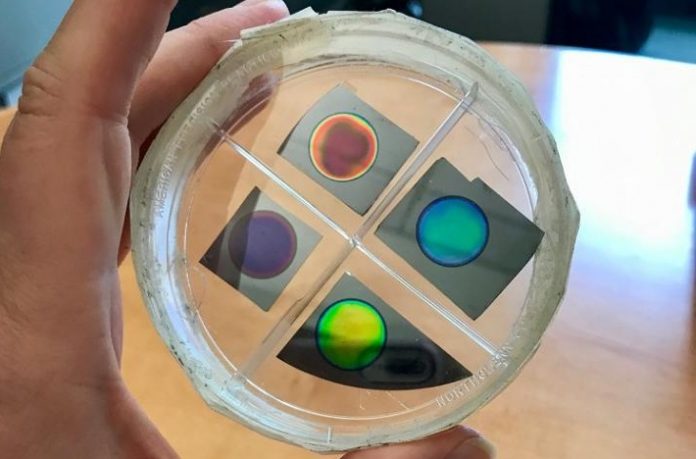

The simplest home medical tests might look like a deck of various silicon chips coated in special film, one that could detect drugs in the blood, another for proteins in the urine indicating infection, another for bacteria in water and the like.

Add the bodily fluid you want to test, take a picture with your smart phone, and a special app lets you know if there’s a problem or not.

That’s what electrical engineer Sharon Weiss, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Engineering at Vanderbilt University, and her students developed in her lab, combining their research on low-cost, nanostructured thin films with a device most American adults already own.

“The novelty lies in the simplicity of the basic idea, and the only costly component is the smart phone,” Weiss said.

“Most people are familiar with silicon as being the material inside your computer, but it has endless uses,” she said.

“With our nanoscale porous silicon, we’ve created these nanoscale holes that are a thousand times smaller than your hair. Those selectively capture molecules when pre-treated with the appropriate surface coating, darkening the silicon, which the app detects.”

Similar technology being developed relies on expensive hardware that compliments the smart phone.

Weiss’ system uses the phone’s flash as a light source, and the team plans to develop an app that could handle all data processing necessary to confirm that the film simply darkened with the adding of fluid.

What’s more, in the future, such a phone could replace a mass spectrometry system that costs thousands of dollars.

The Transportation Security Administration owns hundreds of those at airports across the country, where they’re used to detect gunpowder on hand swabs.

Other home tests rely on a color change, which is a separate chemical reaction that introduces more room for error, Weiss said.

Weiss, Ph.D. student Tengfei Cao, and their team used a biotin-streptavidin protein assay and an iPhone SE, model A1662, to test their silicon films and found the accuracy to be similar to that of benchtop measurement systems.

They also used a 3D printed box to stabilize the phone and get standardized measurements for the paper, but Weiss said that wouldn’t be necessary if further research and development led to a commercialized version.

Written by Heidi Hall.

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C9AN00022D.