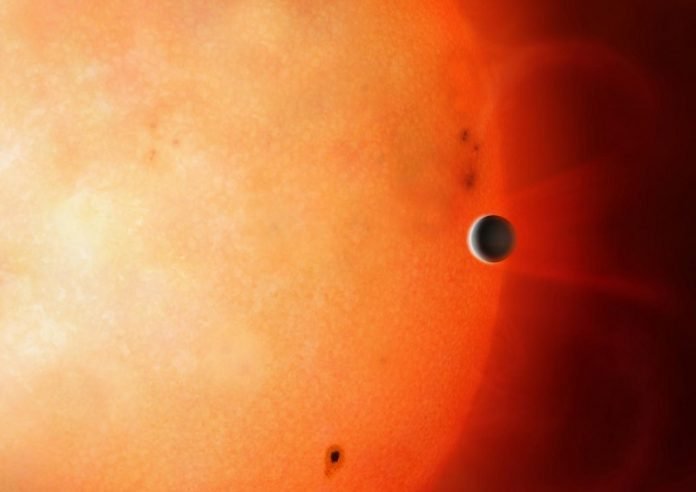

Astronomers have identified a rogue planet orbiting its star in the so-called Neptunian Desert.

The Neptunian Desert is a region close to stars where large planets with their own atmospheres, similar to Neptune, are not expected to survive, since the strong irradiation from the star would cause any gaseous atmosphere to evaporate, leaving just a rocky core behind.

However, NGTS-4b, nicknamed the ‘Forbidden Planet’, still has its atmosphere intact and is the first exoplanet of its kind to be found in the Neptunian Desert.

The results are reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

NGTS-4b is smaller than Neptune and three times the size of Earth.

It is dense and hot, with a mass 20 times that of Earth and an average surface temperature of 1000 degrees Celsius.

The planet orbits its star very closely, completing a full orbit in just 1.3 days.

The planet was identified using the Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) observing facility at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal Observatory in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

NGTS is a collaboration between the Universities of Warwick, Leicester, Cambridge, and Queen’s University Belfast, together with Observatoire de Genève, DLR Berlin and Universidad de Chile.

When looking for new planets, astronomers use facilities such as NGTS to look for a dip in the light of a star, which occurs when an orbiting planet passes in front of it, blocking some of the light.

Usually, dips of 1% and more can be picked up by ground-based searches, but the NGTS telescopes can pick up a dip of just 0.2%.

This sensitivity means that astronomers can now detect a wider range of exoplanets: those with diameters between two and eight times that of Earth, in between the smaller rocky planets and gas giants.

“This is a very rare planet, and it’s the first time that such a small planet has been detected by a wide-field ground-based telescope,” said co-author Dr Ed Gillen from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, who led the data analysis of the system to determine the mass, radius and orbit of NGTS-4b.

The researchers believe the planet may have moved into the Neptunian Desert recently, in the last one million years, or it was very big and the atmosphere is still evaporating.

“This planet must be tough – it is right in the zone where we expected Neptune-sized planets could not survive,” said lead Dr Richard West from the University of Warwick.

“It is truly remarkable that we found a transiting planet via a star dimming by less than 0.2% – this has never been done before by telescopes on the ground, and it was great to find after working on this project for a year.

“We are now searching our data for other similar planets to help us understand how dry this Neptunian Desert is, or whether it is greener than was once thought,” said Gillen.

The research was supported in part by the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz1084.