The subsurface ocean of Saturn’s moon Enceladus probably has higher than previously known concentrations of carbon dioxide and hydrogen and a more Earthlike pH level.

This possibly provides conditions favorable to life, according to new research.

The presence of such high concentrations could provide fuel—a sort of chemical “free lunch”—for living microbes, says lead researcher Lucas Fifer, a doctoral student in earth and space sciences at the University of Washington.

Or, it could mean “that there is hardly anyone around to eat it.”

The new information about the composition of Enceladus’ ocean gives planetary scientists a better understanding of the ocean world’s capacity to host life, Fifer says.

Oceans on Enceladus

Enceladus is a small moon, an ocean world about 310 miles (500 kilometers) across. Its salty subsurface ocean is of interest because of the similarity in pH, salinity, and temperature to Earth’s oceans.

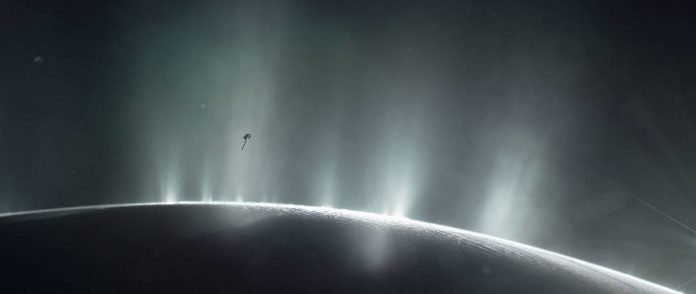

Plumes of water vapor and ice particles—which the Cassini spacecraft spotted and studied—erupting hundreds of miles into space from the ocean through cracks in Enceladus’s ice-encased surface provide a tantalizing glimpse into what the moon’s subsurface ocean might contain.

But Fifer and colleagues found that the plumes aren’t chemically the same as the ocean from which they erupt at 800 miles an hour; the eruption process itself changes their composition.

Fifer and colleagues say the plumes provide an “imperfect window” to the composition of Enceladus’s global subsurface ocean and that the plume composition and ocean composition could be much different.

That, they find, is due to plume fractionation, or the separation of gases, which preferentially allows some components of the plume to erupt while others are left behind.

This in mind, the team returned to data from the Cassini mission with a computer simulation that accounts for the effects of fractionation, to get a clearer idea of the composition of Enceladus’s inner ocean’s.

They found “significant differences” between Enceladus’s plume and ocean chemistry. Previous interpretations, they found, underestimate the presence of hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide in the ocean.

Potential fuel for life

“It’s better to find high gas concentrations than none at all,” says Fifer. “It seems unlikely that life would evolve to consume this chemical free lunch if the gases were not abundant in the ocean.”

Those high levels of carbon dioxide also imply a lower and more Earthlike pH level in the ocean of Enceladus than previous studies have shown. This bodes well for possible life, too, Fifer says.

“Although there are exceptions, most life on Earth functions best living in or consuming water with near-neutral pH, so similar conditions on Enceladus could be encouraging,” he says.

“And they make it much easier to compare this strange ocean world to an environment that is more familiar.”

There could be high concentrations of ammonium as well, which is also a potential fuel for life. And though the high concentrations of gases might indicate a lack of living organisms to consume it all, Fifer says, that does not necessarily mean Enceladus is devoid of life.

It might mean microbes just aren’t abundant enough to consume all the available chemical energy.

The researchers can use the gas concentrations to determine an upper limit for certain types of possible life that could exist in the icy ocean of Enceladus.

In other words, he says: “Given that there’s so much free lunch available, what’s the greatest amount that life could be eating to still leave behind the amount we see? How much life would that support?”

Thanks to Cassini, he says, we know about Enceladus’ ocean and the types of gases, salts, and organic compounds that are present there. Studying how the plume composition changes can teach us yet more about this ocean and everything in it.

“Future spacecraft missions will sample the plumes looking for signs of life, many of which will be affected just by the eruption process,” Fifer says. “So, understanding the difference between the ocean and the plume now will be a huge help down the road.”

The researchers will present their work at the astrobiology conference AbSciCon2019.

Written by Peter Kelley.