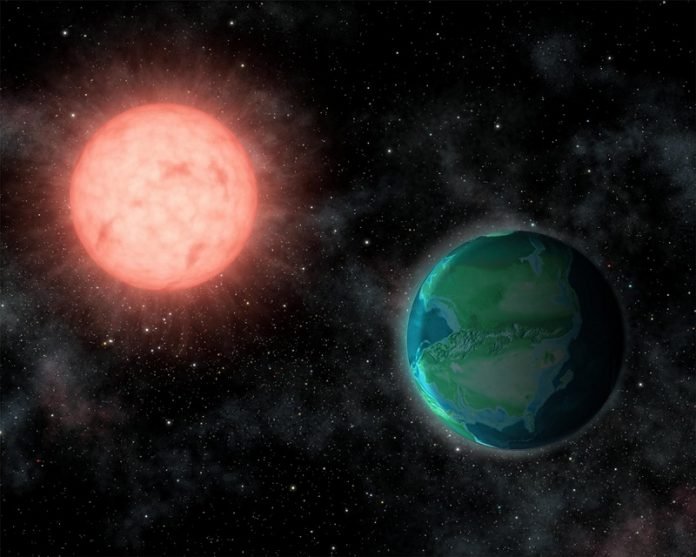

In a new study, researchers found that Earth-like planets orbiting our closest stars may host life.

They suggest that life may be evolving on these exoplanets now.

The study was done by a team from Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute.

In the study, the team focused on Proxima-b, or Proxima Centauri b, which is an exoplanet orbiting in the habitable zone of the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri.

Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the Sun and part of a triple star system.

Proxima-b is located about 4.2 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Centaurus. This makes it the closest known exoplanet to the Solar System.

Previous research has shown that Proxima-b receives 250 times more X-ray radiation than Earth and that it could experience deadly levels of ultraviolet radiation.

Such environmental conditions make life hard to survive.

However, the researcher suggests that life already has survived this kind of fierce radiation.

According to them, all of life on Earth has evolved from creatures that thrived during an even greater UV radiation than Proxima-b.

The same thing could be happening on some of the nearest exoplanets.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers modeled the surface UV environments of the four exoplanets.

All of the four exoplanets closest to Earth are potentially habitable, including Proxima-b, TRAPPIST-1e, Ross-128b, and LHS-1140b.

These planets orbit small red dwarf stars that flare frequently and bathe their planets in high-energy UV radiation.

Such flares can be biologically damaging and cause erosion in planetary atmospheres.

Research has shown that high levels of radiation can cause biological molecules like nucleic acids to mutate or even shut down.

In their experiments, the team modeled various atmospheric compositions.

The models show that as atmospheres thin and ozone levels decrease, more high-energy UV radiation reaches the ground.

The researchers then compared the models with Earth’s history from nearly 4 billion years ago to today.

They found that the modeled planets receive higher UV radiation than that emitted by our own sun today, but the levels are much lower than what Earth received 3.9 billion years ago.

The findings suggest that if life can survive in a much harsher environment on Earth, it is possible that life is evolving on the exoplanets.

Future work needs to confirm these results.

The researchers of the study are Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy and director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute; and Jack O’Malley-James, a research associate.

The study is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Copyright © 2019 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.