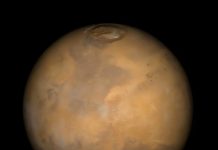

A Mars trip is a long journey. How to stay mentally healthy during the long trip is an important issue.

Between 2007 and 2011, Russia, the European Space Agency and China conducted the Mars-500 project – an experiment on a space travel simulator – to examine the impact of psychological isolation on people’s mental health during a deep space mission.

Six males aged 28 – 37 participated in the study. Their backgrounds included engineering, biology, medicine, and human spaceflight.

All crew members lived and worked in a mock-up spacecraft.

The main phases in the 520-day simulation consisted of starting the simulation, traveling to Mars, landing on Mars, doing activities on Mars, returning to Earth, and completing the project.

After the project, researchers invited each crew member to tell a story about his experience.

Many members mentioned that their goals were to learn about space missions, meet new scientists from the world, learn new scientific methods, and earn money.

Crew members also described their technical adaptation of the Mars trip, and some mentioned a “feeling-down” mood due to the repetition of the experiment every day.

Outside news (e.g., a mining accident in Chile), emergency situations, and celebrations (e.g., birthdays) created breaks in monotony and made crew members feel better.

Undoubtedly, the peak experience came when they reached Mars. All the members were very excited and believed that it was worth the hard work.

After 30 days of the Mars work, they started to return to Earth. Crew members needed to fill questionnaires, finish health checks, and complete physiological measurements. Their mood and motivation declined, and outside news influenced their emotions.

During the return to Earth, members had a new food to eat, and it opened ways to other topics, such as culture and history. Crew members perceived cultural differences positively.

Language differences caused some problems at the beginning of the trip, but later members could understand each other with verbal and non-verbal communication.

At the end of the simulation trip, members could contact their families and close friends by phone. This improved the team’s mood, and they knew that life isolation would come to an end soon.

Researchers concluded that the team handled the long trip in good psychological shape under the tough conditions: restriction of food and information, little fresh air, no nature and sunlight, and separation from their loved ones.

This 520-day mission yielded important data on the physiological, social and psychological effects of long-term isolation in an interplanetary trip.